Dell dropped a 10.0 CVSS advisory today, and if you have RecoverPoint for Virtual Machines anywhere in your environment, this one requires immediate attention. Not “schedule a change window” attention. Not “put it in the next sprint” attention. Right now attention.

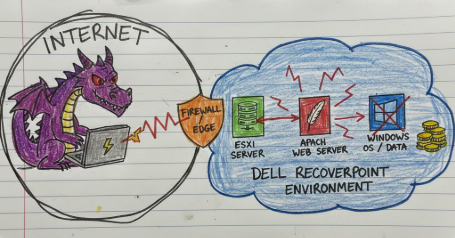

CVE-2026-22769 is a hardcoded credential vulnerability in Dell RecoverPoint for Virtual Machines (RP4VM). The short version: a set of static admin credentials were baked directly into Apache Tomcat’s tomcat-users.xml config file, sitting readable on disk, unchanged across every deployment. Any unauthenticated attacker who can reach port 8443 (or wherever Tomcat is listening) and knows the credential string gets immediate access to the Tomcat Manager interface, from which they can deploy arbitrary WAR files and run commands as root on the appliance.

Ten out of ten. No authentication required. No user interaction. Scope changed. The CVSS vector says everything you need to know: AV:N/AC:L/PR:N/UI:N/S:C/C:H/I:H/A:H. That’s a clean sweep.

And the kicker? Mandiant and the Google Threat Intelligence Group didn’t discover this through a code audit. They found it during incident response while a PRC-linked threat cluster called UNC6201 was actively using it in the wild. The credential was hardcoded. The attackers knew it. Your vendor didn’t tell you.

The Vulnerability

RecoverPoint for Virtual Machines is a Dell/EMC disaster recovery product that sits inside VMware environments and manages continuous data replication and point-in-time recovery for VMs. It ships as a virtual appliance, meaning it’s a pre-built Linux VM with all the required software already installed, deployed into your vSphere environment where it promptly gets assigned a static IP, a DNS record, firewall rules, and then largely forgotten about.

The appliance runs Apache Tomcat as its internal web server to handle the deployment and management of various RecoverPoint software components. Tomcat Manager is the standard Tomcat admin interface used to deploy, undeploy, and manage web applications packaged as WAR (Web Application Archive) files. Dell uses this internally for RecoverPoint’s own component deployment.

The problem is in /home/kos/tomcat9/tomcat-users.xml. This file defines the users and roles for Tomcat Manager authentication. In every version of RecoverPoint for Virtual Machines prior to 6.0.3.1 HF1, this file contains a hardcoded credential for the admin user with the manager-gui and manager-script roles. The credential does not change between deployments. It does not rotate. It is identical across every single RecoverPoint appliance ever deployed.

This is CWE-798 in its purest form. Someone wrote a static password into a config file during development, it shipped to production, and then it shipped to every customer who ever deployed the product.

The exploitation path is straightforward:

- Authenticate to Tomcat Manager using the hardcoded credential

- Upload a malicious WAR file via the

/manager/text/deployendpoint - The WAR deploys and its contents execute with the privileges of the Tomcat process

- On RecoverPoint appliances, Tomcat runs as root

That’s it. No exploitation chain. No memory corruption. No race conditions. You log in with a password that was written into a config file on a build server years ago and you get root on an appliance that sits inside a trusted VMware environment with full access to the virtual infrastructure it manages.

Timeline and Abuse History

This one was a zero-day for a while. A long while.

- Mid-2024: UNC6201 begins exploiting CVE-2026-22769 in the wild. At this point there is no CVE, no advisory, no patch. The credential has been hardcoded in the product for an unknown period prior to exploitation.

- Mid-2024 to September 2025: UNC6201 deploys BRICKSTORM (a Go/Rust-written backdoor) on compromised RP4VM appliances via this vulnerability. Activity is observed across multiple victim organizations.

- September 2025: UNC6201 begins replacing BRICKSTORM binaries with a new C# backdoor tracked as GRIMBOLT. Whether this is a planned capability upgrade or a direct response to Mandiant’s IR activities is unclear.

- Late 2025/Early 2026: Mandiant and Google GTIG investigate multiple RP4VM appliances in victim environments with active C2. Analysis of Tomcat configuration files surfaces the hardcoded credential and the exploitation method.

- February 17, 2026: Dell publishes DSA-2026-079. CVE-2026-22769 is assigned. Patch is available. Mandiant and GTIG publish their full technical write-up the same day.

The gap between first exploitation (mid-2024) and public disclosure (February 2026) is approximately 18 months. During that window, UNC6201 had essentially unlimited time to deploy malware, establish persistence, pivot through VMware infrastructure, and adapt their tooling without vendors or defenders knowing the initial entry point existed.

Impacted Versions and Patch Status

Affected Products:

RecoverPoint for Virtual Machines is the only affected product. RecoverPoint Classic (physical and virtual appliances) is explicitly noted as not affected by Dell’s advisory.

Every version of RecoverPoint for Virtual Machines prior to 6.0.3.1 HF1 is vulnerable. Dell specifically calls out the following:

| Version | Status |

|---|---|

| 5.3 SP2, 5.3 SP3, 5.3 SP4 | Vulnerable (potentially earlier too) |

| 5.3 SP4 P1 | Vulnerable |

| 6.0, 6.0 SP1, 6.0 SP1 P1, 6.0 SP1 P2 | Vulnerable |

| 6.0 SP2, 6.0 SP2 P1 | Vulnerable |

| 6.0 SP3, 6.0 SP3 P1 | Vulnerable |

| 6.0.3.1 HF1 | Patched |

Remediation options:

For versions 6.0 through 6.0 SP3 P1: upgrade directly to 6.0.3.1 HF1, or apply the Dell remediation script documented in KB article 000426742.

For version 5.3 SP4 P1: migrate to 6.0 SP3 first, then upgrade to 6.0.3.1 HF1. Or apply the remediation script.

For 5.3 SP4 and earlier: upgrade to 5.3 SP4 P1 first, then follow the above path. Dell acknowledges that earlier 5.3 versions are also impacted.

The remediation script path is the faster option if you cannot afford the downtime of a full version upgrade right now. But the upgrade is the right long-term answer.

Proof of Concept Details

No standalone public PoC has been released as of the time of this writing. The Mandiant/GTIG disclosure covers the exploitation method in sufficient detail that this will likely change quickly, but right now you’re not looking at script-kiddie-level mass exploitation. You’re looking at nation-state level targeted exploitation that has been happening for 18 months already.

The conceptual PoC is embarrassingly simple. Given the hardcoded credential (not published here, but present in the tomcat-users.xml file on any unpatched appliance), exploitation looks like this:

Step 1: Verify Tomcat Manager is accessible

curl -v https://<target>:8443/manager/html -u admin:<hardcoded_password>

A 200 response with the Tomcat Manager UI confirms the credential works.

Step 2: Deploy a malicious WAR via the text interface

curl -v -u admin:<hardcoded_password> \

-T /path/to/shell.war \

"https://<target>:8443/manager/text/deploy?path=/shell&update=true"

Step 3: Access the deployed web shell

curl "https://<target>:8443/shell/cmd.jsp?c=id"

Response: uid=0(root) gid=0(root) groups=0(root)

In the real-world UNC6201 campaigns, the deployed WAR contained a SLAYSTYLE web shell, which is a JSP-based shell that accepts base64-encoded commands, executes them via Runtime.getRuntime().exec(), and returns the output. The specifics of SLAYSTYLE’s command encoding are documented in the Mandiant report IOC section.

Exploitation Analysis

Let’s walk through what actually happens technically when this vulnerability is exploited, and why it’s so clean.

Apache Tomcat Manager and WAR Deployment

Apache Tomcat Manager is a standard web application that ships with Tomcat and provides a web-based interface for deploying and managing web applications. It’s protected by role-based authentication defined in tomcat-users.xml. The relevant roles for exploitation are manager-gui (web UI access) and manager-script (text API access, used by build automation).

The /manager/text/deploy endpoint accepts an HTTP PUT request with a WAR file as the request body, plus URL parameters that define the deployment context path and whether to overwrite an existing deployment. This endpoint is designed for CI/CD pipeline automation. In RecoverPoint’s case, it’s used for Dell’s own component deployment during product updates. There is no additional authorization layer beyond the Tomcat Manager credentials.

The Hardcoded Credential Location

Mandiant’s analysis pinpointed the credential in /home/kos/tomcat9/tomcat-users.xml. The kos directory is the home directory for the RecoverPoint operating environment. A tomcat-users.xml file with hardcoded credentials in this location would look something like:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<tomcat-users xmlns="http://tomcat.apache.org/xml"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://tomcat.apache.org/xml tomcat-users.xsd"

version="1.0">

<role rolename="manager-gui"/>

<role rolename="manager-script"/>

<role rolename="admin-gui"/>

<user username="admin" password="<HARDCODED_VALUE>"

roles="manager-gui,manager-script,admin-gui"/>

</tomcat-users>

Because RecoverPoint ships as a pre-built appliance OVA/VMDK, this file is identical on every single deployed instance. Every customer who ever deployed RecoverPoint for Virtual Machines has the same password in that file unless they applied the patch or remediation script.

WAR File Deployment as Root Code Execution

WAR files are Java web application archives. When deployed to Tomcat, they are extracted and the web application they contain becomes accessible at the specified context path. Any JSP files within the WAR are compiled on first access and executed by the Tomcat JVM process.

The critical piece here is process privilege. The Tomcat server process on the RecoverPoint appliance runs as root. This is not unusual for appliance-style deployments where the vendor controls the entire OS stack, but it means that any code executed via the Tomcat process, including code in a malicious deployed WAR, runs with full root privileges on the Linux appliance.

This bypasses any sandboxing or privilege separation that might otherwise limit the blast radius of a compromised web application component. There is no seccomp profile to escape, no container boundary to cross. You authenticate to Tomcat Manager, you upload a WAR, you have root on the box.

SLAYSTYLE Web Shell

The web shell UNC6201 deployed via this vulnerability is SLAYSTYLE, a JSP-based backdoor. Based on the YARA rule published by GTIG, SLAYSTYLE’s key characteristics include:

- JSP page import of

java.io - Use of

Base64.getDecoder().decode()to decode command input, specifically usingc.substring(1)to strip a leading byte from the encoded command - Command execution via

Runtime.getRuntime().exec()with/bin/sh -c - Output capture via

ByteArrayOutputStream

The base64 encoding of commands provides minimal obfuscation but makes the web shell less likely to trigger simple string-matching signatures on command parameters. The shell takes POST requests with an encoded command parameter, executes the decoded string via shell, and returns output. Because the Tomcat process runs as root, every command executes with root privileges.

BRICKSTORM and GRIMBOLT Persistence

Once SLAYSTYLE provides interactive access, UNC6201’s next step in observed campaigns was deploying persistent backdoors.

BRICKSTORM is a multi-version backdoor (written in Go in early versions, later ported to Rust) that provides a reverse-shell capability and communicates with attacker-controlled C2 infrastructure. In the RP4VM context, BRICKSTORM was placed as a binary on disk and persistence was established by modifying /home/kos/kbox/src/installation/distribution/convert_hosts.sh, a legitimate shell script that is executed at boot time via rc.local. Adding the backdoor binary path to this script ensures it starts automatically on every reboot without adding new cron jobs, new systemd services, or other persistence mechanisms that might attract attention in a security audit.

In September 2025, UNC6201 began replacing BRICKSTORM with GRIMBOLT on already-compromised appliances. GRIMBOLT is written in C# and compiled using .NET Native AOT compilation. Native AOT, introduced to .NET in 2022, compiles C# code directly to native machine code at build time rather than producing intermediate language (CIL) bytecode that is JIT-compiled at runtime. The consequences for defenders are significant: there is no CIL metadata in the binary, which means standard .NET reverse engineering tools that parse IL metadata are largely ineffective. The binary also bundles all required libraries, so there are no external DLL dependencies to trace. On top of Native AOT, the binary is packed with UPX, adding another layer of static analysis friction.

GRIMBOLT uses the same WebSocket-based C2 protocol as BRICKSTORM, communicating with wss://149.248.11.71/rest/apisession, and provides a remote shell capability. The persistence mechanism is identical: the convert_hosts.sh modification that was used for BRICKSTORM is updated to point to the GRIMBOLT binary instead.

Ghost NICs and VMware Pivoting

The post-exploitation tradecraft UNC6201 employs once inside the RP4VM appliance is where things get genuinely novel. The RecoverPoint appliance has privileged access to the VMware vCenter environment it manages by design. That access becomes a pivot point.

The most interesting newly observed technique is the creation of “Ghost NICs.” UNC6201 creates new temporary virtual network interface cards on existing VMs running on ESXi hosts. These NICs are added dynamically via the VMware APIs that the RecoverPoint appliance has access to, connected to internal network segments, and used to establish connections to additional targets within the environment, including internal services and SaaS environments. After the pivoting activity is complete, the NICs are removed, leaving minimal trace in VM configuration history.

This is a technique Mandiant states they have not observed in prior investigations. It leverages the trusted relationship between the backup/DR appliance and the hypervisor, an access pattern that defenders rarely monitor closely, to enable stealthy lateral movement without touching the guest OS network stack in a persistent way.

The second novel technique is Single Packet Authorization (SPA) implemented via iptables rules on compromised vCenter appliances. The observed iptables configuration monitors incoming traffic on port 443 for a specific hex string in the packet payload. When the magic string is detected, the source IP is dynamically added to an allowed list. Subsequent connections from that IP to port 10443 are accepted, and for a 300-second window, traffic to port 443 is automatically redirected to 10443. This means the backdoor listener on port 10443 is effectively invisible unless you know the knock sequence. Standard port scans won’t see it. Firewall rule reviews won’t flag it. The listener only becomes active in response to a correctly crafted packet.

Forensic Evidence Collection

If you’re dealing with a suspected or confirmed compromise of a RecoverPoint for Virtual Machines appliance, here’s what to collect and where to find it.

Disk Image

The appliance runs as a VM, which means you can snapshot it at the hypervisor layer without touching the guest OS.

VMware ESXi:

# Suspend the VM first to get a consistent image

vim-cmd vmsvc/power.suspend <vmid>

# Copy the VMDK

vmkfstools -i /path/to/rp4vm.vmdk /forensics/rp4vm-forensic.vmdk

# Or use the vCenter export function for a clean OVA snapshot

Via vSphere API:

Use the CreateSnapshot task on the VM object to create a quiesced snapshot, then export the VMDK from the snapshot delta file for imaging.

If you cannot take the VM offline, use a live backup instead:

dd if=/dev/<source_disk> bs=4M | ssh forensics@<collection_host> "dd of=/forensics/rp4vm.img bs=4M"

Memory

Memory acquisition of the RP4VM appliance can be done at the hypervisor level. The VM’s memory is the most volatile artifact and should be collected before anything else if active C2 activity is suspected.

VMware snapshot (includes memory):

vim-cmd vmsvc/snapshot.create <vmid> "forensic-snap" "Memory snapshot for IR" 1 0

# The .vmss or .vmsn file in the VM directory contains the memory state

AVML from within the guest (if you have SSH access):

./avml --compress /tmp/memory.lime

scp /tmp/memory.lime forensics@<collection_host>:/forensics/

KVM/QEMU (if running on KVM rather than VMware):

virsh dump <domain_name> /forensics/rp4vm-memory.dump --memory-only --live

Log Data

Tomcat Manager audit log (highest priority):

/home/kos/auditlog/fapi_cl_audit_log.log

This is where you will find any requests to /manager. Any PUT /manager/text/deploy requests in this log should be treated as a primary IOC. Pay close attention to the deployment path parameter, which reveals where a potentially malicious WAR was dropped.

Tomcat application logs:

/var/log/tomcat9/catalina.out

/var/log/tomcat9/localhost.<date>.log

Look for org.apache.catalina.startup.HostConfig.deployWAR events. The localhost log contains WAR deployment events and any exceptions generated by malicious web applications post-deployment.

Deployed WAR files:

/var/lib/tomcat9/webapps/

This is where deployed WAR files land. Any directory here that you did not put there is suspicious. SLAYSTYLE and similar web shells will be present as a directory containing a .jsp file (and a .java source file if it compiled successfully).

Compiled WAR artifacts:

/var/cache/tomcat9/Catalina/

Even if the attacker deleted the WAR file and the deployed directory, compiled artifacts may persist here.

Persistence mechanism:

/home/kos/kbox/src/installation/distribution/convert_hosts.sh

Check this file for any modifications that reference external binary paths. Legitimate RecoverPoint deployments do not add extra commands to this script. Any addition here is a direct indicator of BRICKSTORM or GRIMBOLT persistence.

rc.local:

/etc/rc.local

Verify that rc.local still calls convert_hosts.sh and nothing else unexpected.

Deployed backdoor binaries: Search common paths used by the actor:

find /tmp /var/tmp /home /opt -type f -name "*.elf" -o -name "support" -o -name "splisten" 2>/dev/null

System authentication logs:

/var/log/auth.log

/var/log/secure

Look for SSH logins, su activity, and any failed/successful authentication events correlated with the compromise window.

Web server request logs:

If the appliance has access logging enabled on the Tomcat level, HTTP request logs will be in /var/log/tomcat9/. Access logs will show GET/POST requests to deployed web shells after WAR deployment.

External Log Sources

If you’re lucky enough to have the appliance shipping logs to a SIEM:

Check for HTTP POST requests to https://<appliance_ip>:8443/manager/text/deploy in your proxy or network logs. The external visibility into Tomcat Manager requests is your best out-of-band validation source. Also check for network connections from the appliance IP to the known GRIMBOLT C2 149.248.11.71 on port 443 via WebSocket.

Considerations and Limitations

Here’s the part where we talk about what you’re not going to find and why this investigation is harder than it looks.

The credential exposure window is undetectable in retrospect. There’s no logging of failed authentication attempts to Tomcat Manager by default. If an attacker scanned your environment to verify the credential was valid and then came back later to exploit it, you will have no record of the reconnaissance phase. The first forensic artifact is the successful WAR deployment, by which point the access is already established.

WAR deployment logs rotate. The Tomcat audit log at /home/kos/auditlog/fapi_cl_audit_log.log is not guaranteed to retain entries from mid-2024. If this compromise started a year or more ago as Mandiant’s timeline suggests, early exploitation evidence is likely gone from the appliance itself. Your SIEM is the only hope for the initial access timeline, and only if you were shipping logs from the appliance, which most organizations are not.

The attacker can modify the audit log. They have root. They can edit, truncate, or delete any log file on the appliance. In cases where an attacker was active for months before detection, assume the log files have been tampered with. Hash verification against known-good states is not possible without a pre-compromise baseline, which nobody has.

GRIMBOLT’s Native AOT compilation defeats standard static analysis. Without CIL metadata, tools like dnSpy, ILSpy, and dotPeek provide minimal insight. FLARE’s analysis relied on dynamic analysis and pattern matching via YARA against native binary artifacts. If you find the binary but can’t analyze it in your environment, submit it to a sandbox that supports native Linux ELF analysis.

Ghost NICs are ephemeral. The temporary virtual network interfaces UNC6201 creates on ESXi VMs are added and removed dynamically. vCenter event logs (Tasks and Events in the vSphere client) should show ReconfigVM_Task events for NIC additions and removals, but the retention period depends on your vCenter configuration. Default retention is 30 days. For a compromise that started in mid-2024, that evidence is long gone.

The iptables SPA configuration is runtime-only. The iptables rules observed on compromised vCenter appliances are loaded into the running kernel’s firewall state. They are not written to persistent iptables config files. A reboot of the vCenter appliance would clear them. This means if your first response action was to restart a suspicious-looking vCenter VM, you may have already eliminated this forensic artifact.

BRICKSTORM-to-GRIMBOLT replacement destroys prior artifact. In cases where UNC6201 replaced BRICKSTORM with GRIMBOLT in September 2025, the BRICKSTORM binary was removed. The GRIMBOLT binary is the only malware artifact remaining. The convert_hosts.sh modification is the historical forensic tie that links the current GRIMBOLT deployment to prior BRICKSTORM activity in terms of persistence mechanism, but the malware itself is only the latest iteration.

Fewer than a dozen known victims does not mean fewer than a dozen actual victims. Mandiant knows of less than twelve organizations because those are the ones they responded to or were told about. The full scope of exploitation is unknown. Network appliances without EDR, shipped as pre-built VMs, are exactly the kind of target that gets compromised and stays compromised for years without anyone noticing.

Detection and Hunting

Network-Level Detection

The primary network-level detection opportunity is HTTP traffic to Tomcat Manager from unexpected sources.

Tomcat Manager access from non-management IPs:

Any POST request to https://<rp4vm_ip>:8443/manager/text/deploy from a source IP that is not a known Dell RecoverPoint management host should be treated as a critical alert. This endpoint should never be accessed directly in normal operations outside of vendor-initiated updates.

Check out this Sigma rule: https://github.com/danielgottt/malware-detection-analytics/blob/main/sigma/CVE-2026-22769_1.yml

GRIMBOLT C2 Beacon:

The known C2 endpoint for GRIMBOLT is wss://149.248.11.71/rest/apisession. Any outbound WebSocket connection from a RecoverPoint appliance IP to this host is a confirmed IOC.

WAR file written to Tomcat webapps directory:

Check out this Sigma rule: https://github.com/danielgottt/malware-detection-analytics/blob/main/sigma/CVE-2026-22769_2.yml

VMware-Level Hunting

For Ghost NIC detection, hunt for ReconfigVM_Task events in vCenter event logs where network adapter additions were not initiated by your change management system. Specifically:

- Filter

ReconfigVM_Taskevents from the vCenterTasks and Eventslog - Look for events where the user is the RecoverPoint service account rather than a human admin

- Correlate event timestamps with any other suspicious activity on the RecoverPoint appliance

Also hunt for outbound iptables rules being written on vCenter appliances. If you collect ESXi/vCenter shell history, look for the specific iptables command patterns Mandiant documented, particularly any rule that references --hex-string with a port redirect to 10443.

Remediation and Workarounds

Patch (Preferred)

Upgrade to RecoverPoint for Virtual Machines 6.0.3.1 HF1. Full stop. This is the fix. Everything below is a temporary measure until you get there.

The upgrade path depends on your current version:

- 6.0 through 6.0 SP3 P1: Upgrade directly to 6.0.3.1 HF1

- 5.3 SP4 P1: Migrate to 6.0 SP3 first, then upgrade to 6.0.3.1 HF1

- 5.3 SP4 and earlier: Upgrade to 5.3 SP4 P1, then follow the 5.3 SP4 P1 path above

Dell Remediation Script (Faster Alternative)

Dell published a standalone remediation script in KB article 000426742 that addresses the hardcoded credential without requiring a full version upgrade. This is the right choice if you need to close the vulnerability immediately and cannot afford upgrade downtime right now. Apply it, then schedule the upgrade.

Network Segmentation (Mitigation, Not Remediation)

Dell’s advisory notes that RecoverPoint for Virtual Machines is not intended for deployment on public or untrusted networks. If the Tomcat Manager port (typically 8443) is exposed outside of your management network, that exposure is your most urgent problem, more urgent even than the patch.

Firewall rules should ensure that port 8443 on RecoverPoint appliances is only accessible from:

- Specific Dell support IPs during authorized support sessions

- Your vCenter management VLAN

- Nothing else

This does not fix the vulnerability. An attacker who is already inside your network can still exploit it. But it eliminates the remote unauthenticated internet-accessible attack surface.

Hunting for Prior Compromise Before Patching

Before you patch, hunt. Apply the remediation script on a schedule, but in parallel, review the forensic artifacts described above. If UNC6201 was already in your environment, patching the entry point does not remove the backdoor. GRIMBOLT and BRICKSTORM persist through reboots via the convert_hosts.sh modification. You can patch the CVE, reboot the appliance, and wake up with a fully operational backdoor that survived the reboot.

Check convert_hosts.sh first. If it has been modified, you have a persistence issue that is separate from the vulnerability remediation.

Closing Assessment

CVE-2026-22769 is the kind of vulnerability that makes backup infrastructure a liability. The irony is not subtle: the system responsible for recovering your virtual machines from disaster is itself the compromised appliance. The attacker does not need to pop a domain controller, brute force a VPN, or craft an exploit. They log in with a password that was written into a config file and has been sitting there unchanged across every single deployment of the product.

This is not a sophisticated vulnerability. CWE-798 is about as fundamental as it gets in the world of credential security. What makes this notable is the context: a CVSS 10.0 sitting inside a trusted VMware environment, exploited by a PRC-nexus threat cluster for eighteen months before anyone published a CVE, and used as a launchpad for novel post-exploitation techniques including Ghost NICs that Mandiant says they have not seen before.

The UNC6201 playbook here is worth understanding beyond just this CVE. They are specifically targeting appliance-class systems, edge devices, VPN concentrators, backup solutions, DR platforms, anything that lives in a trusted network position, runs a non-standard OS stack, and has no EDR agent on it. These systems are the blind spot in most enterprise security programs. You can have excellent EDR coverage across thousands of Windows endpoints and zero visibility into the Linux VM that manages your entire DR environment.

The threat actor correlation is also worth noting. UNC6201 shows overlaps with UNC5221, which the broader industry tracks as Silk Typhoon. This is not a new actor. Silk Typhoon has been targeting edge infrastructure for years. The baton was effectively passed from Brickstorm to Grimbolt in September 2025, which Mandiant suggests may have been a direct response to IR activity. These actors adapt. They monitor disclosure efforts. They update their tooling in response to detection.

If you run RecoverPoint for Virtual Machines: patch today, apply the remediation script if you cannot patch immediately, audit convert_hosts.sh for modifications, check your SIEM for any connections to 149.248.11.71, and hunt for WAR file deployments in your Tomcat logs going back as far as your retention allows.

And if you were previously targeted by Brickstorm activity in your environment? Per Mandiant’s guidance, go looking for Grimbolt specifically. The switch happened in September 2025. If the attacker was in your environment before that date, there may be a newer backdoor on your RP4VM appliances right now that did not exist the last time you looked.

References

- Dell DSA-2026-079: Security Update for RecoverPoint for Virtual Machines

- Mandiant/GTIG: From BRICKSTORM to GRIMBOLT: UNC6201 Exploiting a Dell RecoverPoint for Virtual Machines Zero-Day

- Cybersecurity Dive: Hackers exploit zero-day flaw in Dell RecoverPoint for Virtual Machines

- BleepingComputer: Chinese hackers exploiting Dell zero-day flaw since mid-2024

- CyberScoop: China Brickstorm Grimbolt Dell Zero-Day

- The Register: Dell 0-day exploited by suspected Chinese snoops since 2024

- VirusTotal GTI IOC Collection