If January is now officially “Ivanti vulnerability month,” CVE-2026-1281 is this year’s opening act, and it’s exactly as bad as you’d expect. Disclosed on January 29, 2026, alongside its sibling CVE-2026-1340, this pre-authentication remote code execution vulnerability in Ivanti Endpoint Manager Mobile (EPMM) was already being actively exploited as a zero-day before anyone outside Ivanti knew it existed. CISA wasted no time adding it to the KEV catalog with a three-day remediation deadline for federal agencies. That’s the government equivalent of yelling “drop everything and fix this immediately.”

The technical sophistication here is genuinely impressive in the worst possible way. Whoever discovered the exploitation technique clearly has an intimate understanding of Bash arithmetic expansion behavior that borders on academic. The watchTowr team put it best: “someone knows Bash far too well, and we love it.” We don’t love the exploitation part, but you have to respect the craft.

Let’s walk through what actually happens when theory meets a production EPMM instance at 2 AM.

CVE Details

CVE-2026-1281: Code injection vulnerability in Ivanti Endpoint Manager Mobile (EPMM) affecting the In-House Application Distribution feature. CVSS 9.8 (Critical).

CVE-2026-1340: Parallel code injection vulnerability affecting the Android File Transfer Configuration feature. Also CVSS 9.8 (Critical).

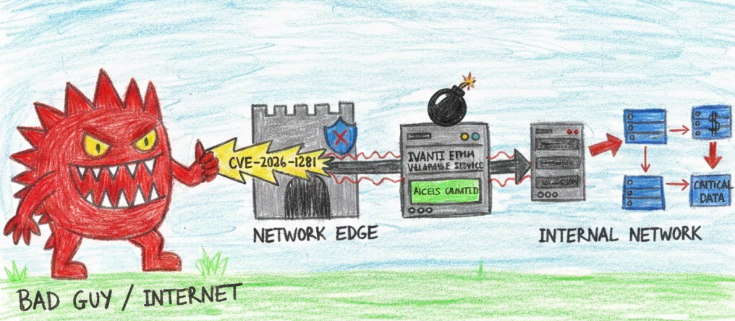

Both allow unauthenticated remote code execution over the network. Attack complexity is low. No privileges required. No user interaction needed. In other words, if your EPMM instance is sitting on the internet, and you haven’t patched, someone is probably already inside.

The vulnerability classification is CWE-94 (Improper Control of Generation of Code). That’s security researcher speak for “user input gets evaluated as code in ways the developers never intended.”

Timeline: Zero-Day to Mass Exploitation

Before January 29, 2026: Unknown threat actors are exploiting CVE-2026-1281 and CVE-2026-1340 in the wild as zero-days. Ivanti later confirms “a very limited number of customers” were compromised. That phrase “very limited” is doing a lot of heavy lifting. The Dutch Data Protection Authority and Council for the Judiciary, the European Commission, and Finland’s Valtori were among confirmed victims.

January 29, 2026: Ivanti releases security advisory and temporary RPM patches. Same day, CISA adds CVE-2026-1281 to the KEV catalog with a February 1 deadline. Three days to patch or disconnect from the network. That’s not a normal patch cycle; that’s a fire drill.

January 30, 2026: watchTowr Labs publishes detailed technical analysis and proof-of-concept code. At this point, the cat is fully out of the bag. Public PoC means automated scanning and mass exploitation is imminent.

February 1, 2026: GreyNoise sensors detect first post-disclosure exploitation attempts. Shadowserver Foundation reports a spike in exploitation traffic from at least 13 source IPs within 24 hours of public disclosure. Approximately 1,600 EPMM instances are exposed globally.

February 8-9, 2026: Exploitation activity escalates sharply. GreyNoise records 269 sessions in a single day, roughly 13 times the daily average. Defused Cyber identifies a campaign deploying dormant in-memory Java class loaders to compromised instances at /mifs/403.jsp. This is initial access broker tradecraft: compromise systems, install sleeper webshells, sell access later.

February 15, 2026: As of this writing, exploitation is ongoing and accelerating. The sleeper shells are designed to wait. Compromised systems may appear fine on the surface while threat actors catalog their inventory for future operations.

Impacted Versions and Patch Status

All on-premises Ivanti EPMM 12.x versions are vulnerable:

- 12.0.0.0 through 12.7.0.0 (all point releases)

Not affected:

- Ivanti Neurons for Mobile Device Management (cloud-hosted)

- Ivanti Endpoint Manager (EPM)

- Ivanti Sentry

- Other Ivanti products

Patch situation: Ivanti released temporary RPM patches that must be manually applied per affected version. These patches do not survive version upgrades and must be reapplied if you perform any maintenance or updates before the permanent fix. The RPM patches are version-specific:

ivanti-security-update-1761642-1.0.0L-5.noarch.rpm(for certain 12.x branches)ivanti-security-update-1761642-1.0.0S-5.noarch.rpm(for other 12.x branches)

The permanent fix is scheduled for EPMM version 12.8.0.0, expected Q1 2026. Until then, you’re managing temporary patches with commitment issues.

Proof of Concept

The exploitation chain is elegant and horrifying. Here’s the path from HTTP request to remote code execution:

- Attacker sends a crafted GET request to the vulnerable endpoint:

GET /mifs/c/appstore/fob/3/5/sha256:kid=1,st=theValue ,et=1337133713,h=gPath[`sleep 5`]/e2327851-1e09-4463-9b5a-b524bc71fc07.ipa

-

Apache’s RewriteRule captures the request and maps it to the Bash script

/mi/bin/map-appstore-urlwith attacker-controlled parameters. -

The Bash script parses the

key=valuepairs from the URL. It extractsst=theValueand stores it in thegStartTimevariable. Note the two trailing spaces intheValueto satisfy a length validation check. -

Later in the script, it extracts

h=gPath[sleep 5]and stores it in thetheValuevariable. -

The script then performs a timestamp comparison:

if [[ ${theCurrentTimeSeconds} -gt ${gStartTime} ]] ; then -

Here’s where the magic happens:

gStartTimecontainstheValue, which now references the last extracted value from the case statement:gPath[`sleep 5`] -

During arithmetic expansion in the comparison, Bash treats

gPathas an array. The array index contains command substitution (sleep 5). The shell executes that command while resolving the index. -

The

sleep 5command executes with the privileges of the web server.

The public PoC demonstrates arbitrary command execution by replacing sleep 5 with id > /mi/poc. Attackers in the wild have used this to deploy webshells, exfiltrate data, and establish persistence.

Technical Analysis: The Exploitation Mechanism

The vulnerability exists in how EPMM handles application distribution requests. The In-House Application Distribution feature uses a Bash script to verify requests and retrieve mobile applications from the approved app store. It requires several parameters:

kid: Index of a salt string from/mi/files/appstore-salt.txtst: Start time for the download operationet: End time for the download operationh: SHA256 hash to verify the caller knows the secret salt- Application GUID to retrieve

Under normal circumstances, this is a straightforward file retrieval with integrity checking. The script validates timestamps, checks the hash, and returns the requested file if everything checks out.

The problem is in how Bash handles indirect variable references during arithmetic expansion. When you write ${gStartTime} in an arithmetic context, and gStartTime contains theValue, Bash dereferences it. If theValue contains an array reference with command substitution like gPath[`command`], the shell executes that command to resolve the array index.

This is not a typical command injection where you’re breaking out of quoted strings or chaining commands with semicolons. This is exploiting the evaluation order of nested variable expansions in arithmetic contexts. It’s the kind of thing you discover by accident after spending hours staring at Bash scripts, or by deeply understanding POSIX shell evaluation semantics.

The CVE-2026-1340 variant works identically but targets the Android File Transfer Configuration feature through /mi/bin/map-aft-store-url. The exploitation mechanics are the same, just a different endpoint: /mifs/c/aftstore/fob/ instead of /mifs/c/appstore/fob/.

Ivanti’s fix replaces both Bash scripts with Java classes (AppStoreUrlMapper.class and AFTUrlMapper.class) that handle URL rewriting without shell interpretation. The entire vulnerability class disappears when you stop passing user input through Bash arithmetic evaluation.

Forensic Evidence Collection

If you’re running EPMM, you need to assume compromise and start collecting evidence immediately. Here’s what you need to preserve:

Apache Access Logs:

/var/log/httpd/https-access_log- This is your primary evidence source for exploitation attempts

- Look for requests to

/mifs/c/appstore/fob/and/mifs/c/aftstore/fob/ - Critical: Export these logs to an external SIEM or collector before doing anything else. Attackers with code execution can and will modify on-box logs.

Apache Error Logs:

/var/log/httpd/error_log- May contain evidence of failed exploitation attempts or command execution errors

System Logs:

/var/log/messages/var/log/secure- Look for unusual process execution, authentication events, privilege escalation

Application Logs:

/mi/logs/directory- EPMM application logs may contain evidence of database access or configuration changes

- Ivanti’s detection RPM generates an

ivanti_checkslog file in the/logdirectory

Process Memory:

- Capture full memory dumps if possible before restarting services

- In-memory webshells do not survive process restarts, so memory forensics is your only chance to identify them

- The

/mifs/403.jspsleeper shells are loaded as Java class loaders in memory

File System:

- Full disk image if you suspect compromise

- Pay special attention to:

/mi/files/(application files)/mi/bin/(scripts and executables)- Web root directories

/tmpand/var/tmp(common staging areas)- Look for files modified around the time of suspicious requests

Database:

- EPMM database backup

- Contains PII for managed mobile devices: names, email addresses, phone numbers, GPS information, device identifiers

- Attackers have been observed extracting this data

Network Traffic:

- Packet captures from the time period before patching

- DNS query logs (attackers have been observed using DNS for C2 communications)

- Outbound connections from the EPMM server

- Particularly suspicious: DNS queries to unusual domains, connections to bulletproof hosting infrastructure

Configuration Files:

- Apache configuration files in

/mi/config-system/xsl/ - EPMM configuration files

- Compare against known-good backups to identify unauthorized modifications

Considerations and Limitations

Let’s talk about what you’re not going to find and why that doesn’t mean you’re safe.

The 404 False Negative: Ivanti’s detection regex looks for 404 responses to vulnerable endpoints. The assumption is that successful exploitation returns a 404 because the requested application file doesn’t actually exist; it’s just a vehicle for command execution. However, this is not foolproof. Attackers can craft requests that return other status codes or legitimate responses while still achieving code execution. Don’t rely solely on 404 detection.

Log Manipulation: Once an attacker has code execution, they can modify logs. If you’re only checking logs on the EPMM server itself, you’re potentially reading fiction. This is why off-box log forwarding to a SIEM or centralized log collector is critical. If you don’t have that, you need to treat all on-box logs as potentially compromised.

In-Memory Implants: The sleeper webshells identified at /mifs/403.jsp are loaded as in-memory Java class loaders. They’re dormant until activated with a specific trigger parameter. They don’t write to disk. They don’t generate obvious network traffic. They just sit there waiting. Memory forensics is the only reliable way to detect these before they activate. Once you restart the application server, they’re gone, and you’ll never know they were there.

Absence of Evidence Is Not Evidence of Absence: The public PoC was released days after exploitation began in the wild. The actual zero-day exploitation may have used different techniques, different payload delivery methods, different persistence mechanisms. Just because you don’t see the known indicators doesn’t mean you weren’t compromised. It means the attackers were more sophisticated than the public exploit.

The Deleted Data Problem: The Dutch Data Protection Authority incident revealed that EPMM doesn’t permanently delete removed data; it just marks it as deleted. This means attackers potentially had access to device and user data for all organizations that ever used the compromised EPMM instance, not just current users. Your forensic scope needs to account for this.

Attribution Uncertainty: The primary exploitation IP identified by GreyNoise (193.24.123.42, AS200593 PROSPERO OOO) is linked to bulletproof hosting infrastructure associated with malware distribution. But IP geolocation reflects where the infrastructure is registered, not where the operator is sitting. Multiple threat actors may be using the same infrastructure. Attribution is murky at best.

Detection and Hunting

Start with the Ivanti-provided regex against Apache access logs:

^(?!127\.0\.0\.1:\d+ .*$).*?\/mifs\/c\/(aft|app)store\/fob\/.*?404

This filters for 404 responses to vulnerable endpoints while excluding legitimate localhost traffic. But as discussed above, this is your baseline, not your conclusion.

Hunt for Bash Command Indicators:

Look for URL-encoded or direct Bash constructs in GET requests:

- Backticks (

`) or$(...)command substitution - Array references with brackets

[...] - Suspicious parameter values in the

st,h, or other fields - Multiple underscores or delimiter characters that suggest parameter injection

Check for the Sleeper Webshell:

find /mifs -name "403.jsp" -type f

Presence of /mifs/403.jsp is a confirmed indicator of compromise. This is the path identified by Defused Cyber for the dormant in-memory class loader campaign.

DNS Analysis:

Attackers are using DNS for C2. Look for:

- Unusual outbound DNS queries from the EPMM server

- High frequency of DNS requests to non-standard domains

- Long subdomain strings that may be encoding data

Review Administrative Actions:

- New or modified EPMM administrator accounts

- Changes to device management policies

- Unauthorized application deployments to managed devices

- Modifications to authentication configurations (LDAP, SAML, etc.)

- Network or security configuration changes

Process Analysis:

If the system is still running (before patching):

- Unexpected Java processes

- Processes spawned by the Apache user

- Unusual parent-child process relationships

- Short-lived processes that may be executing commands and immediately terminating

Network Connections:

- Outbound connections from the EPMM server to unexpected destinations

- Particularly suspicious: connections to known bulletproof hosting ASNs

- As of this writing, GreyNoise has identified 8 unique exploitation source IPs, with 193.24.123.42 accounting for 83% of observed activity

File Integrity Monitoring:

Compare current system state against known-good baselines:

- Bash scripts in

/mi/bin/(should be replaced with Java classes after patching) - Apache configuration files

- Application files in

/mi/files/ - Any unexpected files in system directories

Hunt Across Your Environment:

If one EPMM instance was compromised, threat actors may be moving laterally:

- Check for unusual authentication attempts from the EPMM server’s IP

- Look for credential theft or pass-the-hash attempts

- Review access logs on systems the EPMM instance can reach

- EPMM servers often have privileged access to enterprise resources due to their role in mobile device management

Post-Remediation Validation:

-

Verify the patch applied correctly by checking Apache configuration files in

/mi/config-system/xsl/httpd_ssl_conf.xsl. The RewriteMap directives should point to Java classes, not Bash scripts. -

Test exploitation attempts against your patched instance using the public PoC. If the patch is applied correctly, exploitation attempts should fail. (Use a non-production instance for testing if possible.)

-

Run Ivanti’s detection RPM to generate the

ivanti_checkslog file. Review findings in the context of your broader forensic investigation.

Assume Compromise:

NCSC-NL guidance is clear: all organizations using Ivanti EPMM should assume compromise and conduct a forensic investigation. The zero-day exploitation period before disclosure means you may have been compromised without knowing it. The sleeper webshell campaign means you may be compromised right now and not see any active exploitation. Patching stops future exploitation; it doesn’t undo past compromise.

Closing Assessment

CVE-2026-1281 and CVE-2026-1340 represent everything wrong with how these incidents unfold. Sophisticated zero-day exploitation affecting government and critical infrastructure. Vendor disclosure only after compromise is already in progress. Temporary patches that don’t persist through normal maintenance operations. Public PoC code released within 24 hours. Mass exploitation accelerating daily. Initial access brokers installing sleeper webshells for future operations.

The technical exploitation is genuinely clever. Bash arithmetic expansion abuse through nested variable dereferencing is not something you stumble into by fuzzing. This required either deep understanding of shell evaluation mechanics or an incredible amount of reverse engineering effort. The fact that this was discovered and weaponized as a zero-day suggests a well-resourced threat actor with both technical sophistication and strategic patience.

The forensic implications are sobering. In-memory implants that don’t survive reboots. Log manipulation by attackers with code execution. Deleted data that isn’t actually deleted. Detection gaps during the zero-day exploitation period. Limited indicators of compromise during the sleeper shell phase. This is a nightmare scenario for defenders trying to determine scope of compromise.

If you’re running EPMM, the question is not “were we targeted?” It’s “when were we compromised, and what did they take?” With approximately 1,600 instances exposed globally and confirmed exploitation by initial access brokers, the probability of compromise is high. The time to act was January 29 when the advisory dropped. The next best time is now.

Patch. Investigate. Assume compromise. Harden your defenses. This vulnerability isn’t just another critical RCE; it’s a case study in how sophisticated threat actors exploit enterprise infrastructure at scale.

And for the love of all that is holy, stop passing user input through Bash arithmetic expansion.

References

- Ivanti Security Advisory: CVE-2026-1281 & CVE-2026-1340

- CISA Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog: CVE-2026-1281

- watchTowr Labs Technical Analysis: Someone Knows Bash Far Too Well

- GreyNoise: Active Ivanti Exploitation Traced to Single Bulletproof IP

- Rapid7: Critical Ivanti EPMM Zero-Day Exploited in the Wild

- NVD: CVE-2026-1281