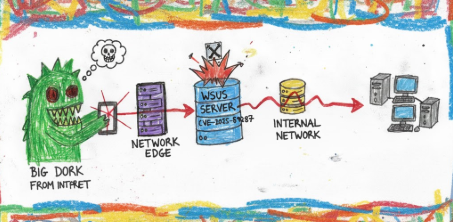

You know that feeling when you realize the system designed to keep your infrastructure secure just became the biggest threat vector in your environment? That’s CVE-2025-59287 in a nutshell. Microsoft’s Windows Server Update Services (WSUS), the very infrastructure meant to deliver security patches to your fleet, became exploitable within hours of public disclosure. And the forensic reality? It’s messier than most people want to admit.

The Vulnerability

CVE-2025-59287 is a critical remote code execution vulnerability affecting Microsoft Windows Server Update Services (WSUS). With a CVSS score of 9.8, this is about as bad as it gets: unauthenticated, network accessible, and trivially exploitable once you understand the mechanics.

The vulnerability exists in WSUS’s reporting web services and stems from a classic .NET deserialization issue. Specifically, the flaw involves the unsafe deserialization of AuthorizationCookie objects sent to the GetCookie() endpoint. The encrypted cookie data is decrypted using AES-128-CBC and then passed directly to BinaryFormatter.Deserialize() without proper type validation. If you’ve been in the trenches long enough, you already know where this is going.

WSUS runs with SYSTEM privileges. Exploitation means immediate, complete compromise of the WSUS server. And because WSUS servers typically have broad network access and trusted relationships across the environment, this is your beachhead for lateral movement.

Timeline: How Fast Things Went Sideways

October 14, 2025: Microsoft disclosed CVE-2025-59287 as part of their October Patch Tuesday. At this point, no active exploitation had been observed, but Microsoft assessed exploitation as “More Likely.” The initial patch was incomplete and didn’t fully address the vulnerability.

October 17, 2025: Security researcher HawkTrace published a detailed proof-of-concept exploit, including working code that demonstrated arbitrary code execution via crafted deserialization payloads. The PoC used ysoserial.net gadget chains to pop calc.exe, showing the path from concept to weaponization.

October 20-21, 2025: Additional PoC code surfaced from multiple sources. The exploit methodology was now public knowledge, complete with encryption routines and SOAP request templates.

October 23, 2025: Microsoft released emergency out-of-band patches for all affected Windows Server versions to fully address the vulnerability. This superseded the incomplete October 14th patch. Within hours of the OOB patch release, active exploitation began. The Dutch National Cyber Security Centre confirmed exploitation activity. Threat actors wasted no time.

October 24, 2025: CISA added CVE-2025-59287 to the Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) catalog, giving federal agencies until November 14th to patch. Multiple security vendors (Eye Security, Huntress, Unit 42, Darktrace) confirmed in-the-wild exploitation with reconnaissance and hands-on-keyboard activity observed.

From disclosure to weaponization to active campaigns: ten days. From emergency patch to exploitation: hours. This is the new normal.

Affected Versions and Patch Status

The vulnerability affects Windows Server systems where the WSUS Server Role is enabled. Critically, this role is not enabled by default, which limited the attack surface but also meant many organizations didn’t know they were running WSUS servers exposed to the internet.

Affected Systems:

- Windows Server 2012 and 2012 R2

- Windows Server 2016

- Windows Server 2019

- Windows Server 2022 (including 23H2 Edition)

- Windows Server 2025

Patch Status:

Microsoft released out-of-band updates on October 23, 2025:

- Windows Server 2025: KB5070881

- Windows Server 2022 23H2: KB5070879

- Windows Server 2022: KB5070884

- Windows Server 2019: KB5070883

- Windows Server 2016: KB5070882

- Windows Server 2012 R2: KB5070886

- Windows Server 2012: KB5070887

Important: The October 14th patches were incomplete. Only the October 23rd out-of-band updates fully mitigate the vulnerability. If you patched on Patch Tuesday and stopped, you’re still vulnerable.

A functional side effect of the patch: WSUS synchronization error details are no longer displayed after installation. Microsoft deliberately removed this functionality to address the vulnerability, which means you’ll need to adjust your monitoring and troubleshooting procedures.

Proof of Concept Details

The HawkTrace PoC demonstrates the exploitation chain with surgical precision. Here’s how it works:

-

Gadget Chain Generation: The exploit leverages ysoserial.net to create a malicious .NET deserialization gadget chain. The default PoC spawns calc.exe, but this is trivially modified to execute arbitrary commands.

-

Serialization: The gadget chain is serialized using

BinaryFormatter. -

Encryption: The serialized payload is encrypted using AES-128-CBC with a hardcoded key (

877C14E433638145AD21BD0C17393071) and a null initialization vector. The encryption uses 16-byte salt prepended to the encrypted data. -

Delivery: The encrypted payload is base64-encoded and embedded in a SOAP request sent to the WSUS ClientWebService endpoint at

/ClientWebService/Client.asmx.

The SOAP request structure looks like this:

POST /ClientWebService/Client.asmx HTTP/1.1

Host: TARGET:8530

Content-Type: text/xml; charset=utf-8

SOAPAction: "http://www.microsoft.com/SoftwareDistribution/Server/ClientWebService/GetCookie"

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<soap:Envelope xmlns:soap="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/envelope/">

<soap:Body>

<GetCookie xmlns="http://www.microsoft.com/SoftwareDistribution/Server/ClientWebService">

<authCookies>

<AuthorizationCookie>

<PlugInId>SimpleTargeting</PlugInId>

<CookieData>[BASE64_ENCRYPTED_PAYLOAD]</CookieData>

</AuthorizationCookie>

</authCookies>

<oldCookie xsi:nil="true" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"/>

<protocolVersion>1.20</protocolVersion>

</GetCookie>

</soap:Body>

</soap:Envelope>

The exploit requires network access to WSUS on its default ports: TCP 8530 (HTTP) or TCP 8531 (HTTPS). Some configurations use TCP 80 or 443 instead.

Technical Deep Dive: The Exploitation Chain

Let’s walk through exactly what happens when an attacker exploits CVE-2025-59287. This is where things get technical.

The Entry Point: GetCookie()

The vulnerability begins in the GetCookie() method of the WSUS Client web service. When a client sends an authorization cookie, it’s processed through several layers:

Client.GetCookie()

→ ClientImplementation.GetCookie()

→ AuthorizationManager.GetCookie()

→ AuthorizationManager.CrackAuthorizationCookies()

→ GenericAuthorizationPlugIn.CrackAuthorizationCookie()

→ EncryptionHelper.DecryptData()

The Vulnerable Code: DecryptData()

The EncryptionHelper.DecryptData() method is where exploitation occurs. Here’s the decompiled logic:

internal object DecryptData(byte[] cookieData)

{

if (cookieData == null)

throw new LoggedArgumentNullException("cookieData");

ICryptoTransform cryptoTransform = this.cryptoServiceProvider.CreateDecryptor();

byte[] array;

try

{

// Validate block size

if (cookieData.Length % cryptoTransform.InputBlockSize != 0 ||

cookieData.Length <= cryptoTransform.InputBlockSize)

{

throw new LoggedArgumentException("Can't decrypt bogus cookieData...");

}

// Decrypt the data

array = new byte[cookieData.Length - cryptoTransform.InputBlockSize];

cryptoTransform.TransformBlock(cookieData, 0, cryptoTransform.InputBlockSize,

EncryptionHelper.scratchBuffer, 0);

cryptoTransform.TransformBlock(cookieData, cryptoTransform.InputBlockSize,

cookieData.Length - cryptoTransform.InputBlockSize,

array, 0);

}

finally

{

cryptoTransform.Dispose();

}

object obj = null;

// Type check

if (this.classType == typeof(UnencryptedCookieData))

{

UnencryptedCookieData unencryptedCookieData = new UnencryptedCookieData();

try

{

unencryptedCookieData.Deserialize(array);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

if (ex is OutOfMemoryException) throw;

throw new LoggedArgumentException(ex.ToString(), "cookieData");

}

obj = unencryptedCookieData;

}

else

{

// THE VULNERABLE PATH

BinaryFormatter binaryFormatter = new BinaryFormatter();

MemoryStream memoryStream = new MemoryStream(array);

try

{

obj = binaryFormatter.Deserialize(memoryStream);

}

catch (Exception ex2)

{

if (ex2 is OutOfMemoryException) throw;

throw new LoggedArgumentException(ex2.ToString(), "cookieData");

}

// Type validation AFTER deserialization

if (obj.GetType() != this.classType)

{

throw new LoggedArgumentException("Decrypted cookie has the wrong data type...");

}

}

return obj;

}

The critical flaw is obvious: BinaryFormatter.Deserialize() is called on attacker-controlled data before any type validation occurs. The type check happens after deserialization, which is too late. By the time the code realizes the object type is wrong, the gadget chain has already executed.

The Gadget Chain

The PoC uses standard ysoserial.net gadget chains, typically leveraging:

System.Collections.Generic.SortedSet<T>with a malicious comparerSystem.DelegateandSystem.Reflectiontypes to chain method invocations- Eventually calling

System.Diagnostics.Process.Start()to execute commands

The serialized payload contains carefully crafted object graphs that abuse .NET’s type system to achieve code execution during deserialization. When BinaryFormatter reconstructs these objects, it invokes constructors and property setters that trigger the payload.

Process Execution Chain

Successful exploitation manifests in one of two process chains, depending on which WSUS component handles the request:

Via IIS Worker Process:

w3wp.exe → cmd.exe → cmd.exe → powershell.exe

Via WSUS Service:

wsusservice.exe → cmd.exe → cmd.exe → powershell.exe

The double cmd.exe invocation is characteristic of the gadget chain execution. Commands are typically base64-encoded PowerShell for obfuscation and payload flexibility.

Alternative Attack Paths

Researchers identified a second exploitation path through the ReportingWebService using SoapFormatter instead of BinaryFormatter. Both formatters suffer from the same fundamental flaw: they deserialize untrusted data without validation. The ReportingWebService path targets event subscription mechanisms and triggers deserialization through the SubscriptionEvent and PopulateSubscriptionEventProperties methods.

Forensic Considerations and Limitations

Now we get to the part that matters for incident response: what forensic artifacts are left behind, and more importantly, what isn’t.

What You’ll Find

IIS Logs (C:\inetpub\logs\LogFiles\W3SVC*\*.log):

Large POST requests to /ClientWebService/Client.asmx or /ReportWebService/ReportWebService.asmx. Look for requests with significantly larger than normal Content-Length headers. The encrypted payloads are typically several kilobytes.

WSUS Application Logs (C:\Program Files\Update Services\LogFiles\SoftwareDistribution.log):

Deserialization errors and exceptions are logged here during exploitation attempts. Specifically, look for stack traces containing:

System.InvalidCastExceptionSystem.Windows.Data.ObjectDataProvider- References to

BinaryFormatter.Deserialize ThreadAbortExceptionentries correlated with exploitation timing

Example from a real exploitation attempt observed by Eye Security:

2025-10-24 06:09:25.952 UTC Warning w3wp.142 SoapUtilities.CreateException

ThrowException: actor = https://host:8531/ClientWebService/client.asmx

The log also contains fragments of base64-encoded serialized payloads starting with the pattern AAEAAAD/////AQAAAAAAAAAEAQAAAH9.

Windows Event Logs:

- Event ID 4688 (Process Creation) in the Security log will show the suspicious process chain: w3wp.exe or wsusservice.exe spawning cmd.exe spawning powershell.exe

- Event ID 7053 in the Application log from the “Windows Server Update Services” provider indicates deserialization errors

Network Traffic: Connections to external infrastructure for command and control or data exfiltration. Observed in the wild:

- Outbound connections to

webhook.sitefor reconnaissance data exfiltration - Connections to

workers.devsubdomains for C2 (e.g.,royal-boat-bf05.qgtxtebl.workers.dev) - HTTP POST requests with PowerShell or cURL user agents

What You Won’t Find (The Forensic Gaps)

Here’s where it gets uncomfortable. CVE-2025-59287 exploitation has several characteristics that make forensic analysis challenging:

Memory-Only Execution: Many exploitation attempts execute entirely in memory. The initial payload delivered via deserialization spawns PowerShell with base64-encoded commands. If the attacker doesn’t drop files to disk, you’re left with volatile memory artifacts that disappear on reboot. Without process memory dumps captured during active exploitation, you might miss critical payload details.

Limited Prefetch Evidence: Because the exploit chain uses native Windows binaries (cmd.exe, powershell.exe) that are already present in prefetch, the artifacts don’t stand out. You’ll see prefetch entries, but they won’t be anomalous by themselves. You need timeline correlation with other indicators.

Minimal File System Footprint: The exploitation itself doesn’t require writing files. The encrypted payload is delivered over HTTP, decrypted in memory, deserialized, and executed. The only disk artifacts are whatever the post-exploitation payload does. If attackers limit themselves to reconnaissance (as observed in early wild exploitation), you might find nothing on disk at all.

Log Rotation and Overwriting:

IIS logs rotate based on size and time. If exploitation occurred days or weeks ago and the logs have rotated, you’ve lost your best forensic evidence. WSUS SoftwareDistribution.log has similar rotation behavior.

Encrypted Network Traffic: If WSUS was configured for HTTPS (port 8531), the encrypted payload and exploitation traffic are within an encrypted channel. Without SSL/TLS interception or endpoint visibility, the network evidence is opaque.

What We’ve Seen In The Wild

Based on public reporting from multiple security vendors, real-world exploitation has followed predictable patterns:

Initial Access (October 23-24, 2025): Attackers scanned the internet for exposed WSUS instances on ports 8530 and 8531. Thousands of WSUS servers were internet-facing due to misconfiguration, despite WSUS being designed for internal use.

Reconnaissance Phase: Post-exploitation PowerShell commands enumerated:

- Domain information (

Get-ADDomain,whoami /all) - Local users and administrators

- Network configuration (

ipconfig /all,Get-NetAdapter) - Running processes and services

- Installed software

This information was exfiltrated to attacker-controlled webhooks using Invoke-WebRequest or cURL.

Persistence and Lateral Movement: In some cases, attackers established persistent C2 using Cloudflare Workers infrastructure. Bitdefender observed secondary-stage payloads being downloaded and executed, indicating this was initial access for larger campaigns (pre-ransomware activity).

Hands-On-Keyboard Activity: Multiple vendors reported interactive operator activity following automated exploitation, suggesting human attackers taking manual control after bots established access.

Detection and Hunting

If you’re reading this section first because you need to hunt for compromise right now, I get it. Here’s what you need to know.

High-Confidence Indicators

Process Creation Monitoring (Windows Event ID 4688 or EDR telemetry):

Look for suspicious child processes of w3wp.exe or wsusservice.exe:

- cmd.exe

- powershell.exe (especially with

-EncodedCommand) - rundll32.exe

- regsvr32.exe

- certutil.exe

- Any unsigned binaries

The double-hop pattern (wsusservice.exe → cmd.exe → cmd.exe → powershell.exe) is highly suspicious.

Base64-Encoded PowerShell:

PowerShell invocations with -EncodedCommand or -enc flags launched from WSUS-related parent processes.

Example hunt query (PowerShell):

Get-WinEvent -LogName Security | Where-Object {

$_.Id -eq 4688 -and

($_.Properties[5].Value -like "*w3wp.exe*" -or

$_.Properties[5].Value -like "*wsusservice.exe*") -and

$_.Properties[8].Value -match "(cmd\.exe|powershell\.exe)"

}

WSUS Application Log Errors:

Query for Event ID 7053 with deserialization-related strings:

Get-WinEvent -FilterHashtable @{

LogName='Application'

ProviderName='Windows Server Update Services'

ID=7053

} | Where-Object {

$_.Message -match "InvalidCastException" -or

$_.Message -match "ObjectDataProvider" -or

$_.Message -match "BinaryFormatter"

}

IIS Log Analysis:

Search for large POST requests to WSUS endpoints:

# Linux/grep approach

grep "POST /ClientWebService/Client.asmx" /path/to/iis/logs/*.log | \

awk '$10 > 5000 {print $0}'

# PowerShell approach

Select-String -Path "C:\inetpub\logs\LogFiles\W3SVC*\*.log" -Pattern "POST.*Client.asmx" |

Where-Object {

($_ -split '\s+')[9] -as [int] -gt 5000

}

Look for the pattern “AuthorizationCookie” in IIS logs:

Network Connections:

Monitor outbound connections from WSUS servers, especially to unexpected destinations:

- Webhook services (webhook.site, pipedream.net)

- Cloudflare Workers domains (*.workers.dev)

- Newly registered domains (registered within last 30 days)

Sigma Rules

The SigmaHQ repository includes two rules specifically for CVE-2025-59287:

WSUS Deserialization Detection:

title: Exploitation Activity of CVE-2025-59287 - WSUS Deserialization

id: e5f66e87-7d6b-404f-92fe-7aa67814b5cd

status: experimental

description: Detects cast exceptions in WSUS application logs indicating CVE-2025-59287 exploitation attempts

references:

- https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/cve-2025-59287/

- https://hawktrace.com/blog/CVE-2025-59287-UNAUTH

logsource:

product: windows

service: application

detection:

selection:

Provider_Name: 'Windows Server Update Services'

EventID: 7053

Data|contains|all:

- 'System.InvalidCastException'

- 'System.Windows.Data.ObjectDataProvider'

- 'Unable to cast object of type'

condition: selection

falsepositives:

- Unlikely

level: high

tags:

- attack.execution

- attack.initial-access

- attack.t1190

- attack.t1203

- cve.2025-59287

- detection.emerging-threats

WSUS Suspicious Child Process:

title: Exploitation Activity of CVE-2025-59287 - WSUS Suspicious Child Process

id: a8d4c3f1-xxxx-xxxx-xxxx-xxxxxxxxxxxx

status: experimental

description: Detects suspicious child processes spawned by WSUS-related parent processes

references:

- https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/cve-2025-59287/

logsource:

product: windows

category: process_creation

detection:

selection:

ParentImage|endswith:

- '\w3wp.exe'

- '\wsusservice.exe'

Image|endswith:

- '\powershell.exe'

- '\cmd.exe'

- '\rundll32.exe'

- '\regsvr32.exe'

- '\certutil.exe'

condition: selection

falsepositives:

- Legitimate administrative activity (low likelihood)

level: high

tags:

- attack.execution

- attack.t1059.001

- attack.t1059.003

- cve.2025-59287

Network-Based Detection

Snort/Suricata Rules:

Snort 2 and Snort 3 both include GID 1, SID 65422 for detecting CVE-2025-59287 exploitation attempts. These signatures identify the specific SOAP request patterns used in exploitation.

If you’re writing custom rules, look for:

- Large POST requests to

/ClientWebService/Client.asmxor/ReportWebService/ReportWebService.asmx - SOAP envelopes containing

<GetCookie>elements with unusually large<CookieData>sections - Base64 data patterns in HTTP POST bodies to WSUS endpoints

- Forensic Artifact Collection:

- Memory dump of WSUS server (if still running)

- IIS logs (preserve before rotation)

- Windows Event Logs (Security, System, Application)

- Network flow data

- EDR/XDR telemetry

Long-Term Security Posture

Architecture Review:

WSUS servers should never be internet-facing. Period. The widespread exploitation of CVE-2025-59287 was possible because thousands of WSUS instances were exposed to the public internet due to misconfigurations.

Best practices:

- WSUS servers should be accessible only from internal management networks

- Require VPN or jump host access for administrative access

- Implement network segmentation with WSUS in a dedicated management VLAN

- Use firewall rules to explicitly allow only necessary traffic

Closing Assessment

CVE-2025-59287 is a case study in how quickly things can go wrong. The vulnerability itself is straightforward: unsafe deserialization with .NET’s BinaryFormatter, a well-known dangerous pattern. The impact is severe: unauthenticated remote code execution as SYSTEM on a critical infrastructure component.

But what makes this particularly painful is the timeline. Microsoft’s initial patch was incomplete. Exploitation began within hours of the corrective OOB patch being released, not because the patch was reverse-engineered, but because the PoC code was already public. By the time most organizations started their patch cycles, attackers had already begun reconnaissance on compromised systems.

From a forensic perspective, this is one of those vulnerabilities where if you’re looking for evidence weeks later, you might find nothing. Memory-only execution, native binary abuse, and log rotation conspire to erase the evidence. The window for detection is narrow.

The broader lesson? Infrastructure services designed for internal use must never be exposed to the internet. Configuration mistakes turn localized vulnerabilities into enterprise-wide disasters. WSUS, SCCM, VMware management interfaces, and similar systems are trusted implicitly by your environment. When they’re compromised, the blast radius is your entire infrastructure.

If you run WSUS, patch now if you haven’t already. Hunt for compromise even if you think you patched in time. The attackers moved fast on this one.

And maybe, just maybe, double-check what else you’ve got listening on 0.0.0.0.

References

-

Microsoft Security Response Center (MSRC), “CVE-2025-59287 - Windows Server Update Service (WSUS) Remote Code Execution Vulnerability,” https://msrc.microsoft.com/update-guide/vulnerability/CVE-2025-59287

-

HawkTrace Security, “CVE-2025-59287 WSUS Remote Code Execution,” October 18, 2025, https://hawktrace.com/blog/CVE-2025-59287

-

Palo Alto Networks Unit 42, “CVE-2025-59287 Exploitation Detected: Vulnerability in Windows Server Update Services Exploited in the Wild,” October 24, 2025, https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/cve-2025-59287/

-

Huntress, “CISA Warns of Actively Exploited Windows WSUS Vulnerability (CVE-2025-59287),” October 24, 2025, https://www.huntress.com/blog/cisa-warns-of-actively-exploited-windows-wsus-vulnerability-cve-2025-59287

-

Eye Security, “WSUS Vulnerability - CVE-2025-59287 - Technical Analysis & Detection,” October 24, 2025, https://eye.security/resources/wsus-cve-2025-59287

-

Bitdefender, “CVE-2025-59287: Actively Exploited Windows Server Update Services Vulnerability,” October 25, 2025, https://www.bitdefender.com/blog/hotforsecurity/cve-2025-59287-actively-exploited-windows-server-update-services-vulnerability/

-

Dutch National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), “Kwetsbaarheden verholpen in Microsoft producten - oktober 2025,” October 23, 2025, https://www.ncsc.nl/actueel/advisory?id=NCSC-2025-0430