The Vulnerability

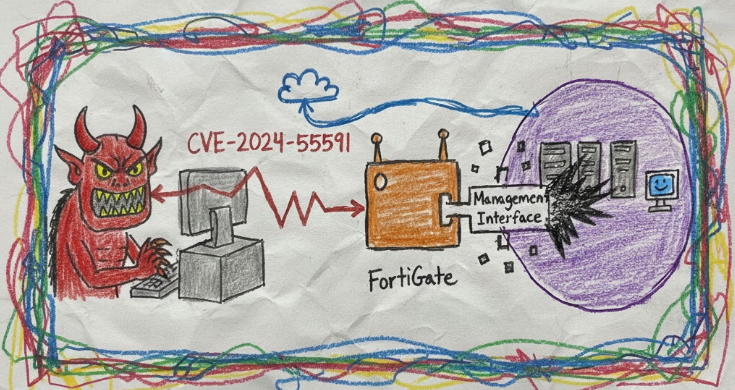

CVE-2024-55591 is what happens when multiple security controls fail simultaneously in a spectacular chain reaction. Fortinet published this as an authentication bypass vulnerability affecting their FortiOS and FortiProxy products, but calling it just an “authentication bypass” is like calling a plane crash “unscheduled ground contact.” This is actually four distinct vulnerabilities holding hands and skipping through your perimeter defenses together.

The vulnerability allows remote, unauthenticated attackers to gain super-admin privileges on FortiGate firewalls and FortiProxy devices by exploiting weaknesses in the Node.js WebSocket module that handles CLI console access. And before you ask, yes, this was being actively exploited in the wild since November 2024, weeks before Fortinet published their advisory.

Timeline

The exploitation timeline tells a familiar story of a zero-day living its best life in the wild before anyone noticed:

- November 2024: Arctic Wolf begins tracking suspicious activity on FortiGate devices, observing unauthorized administrative logins from the

jsconsoleinterface. At this point, nobody knew what they were looking at. - December 17, 2024: Arctic Wolf releases a bulletin recommending organizations disable publicly exposed management interfaces. Still no CVE, just a polite suggestion that maybe your firewall’s admin panel shouldn’t be on the internet.

- January 14, 2025: Fortinet finally publishes advisory FG-IR-24-535, assigning CVE-2024-55591. They confirm active exploitation and release patches. The advisory notes that attackers need to know a valid admin username, which sounds reassuring until you remember that “admin” is still the most popular admin username in 2025.

- January 15, 2025: CISA adds CVE-2024-55591 to the Known Exploited Vulnerabilities catalog, setting a remediation deadline of January 21, 2025.

- January 27, 2025: watchTowr Labs publishes detailed technical analysis and releases public proof-of-concept code. At this point, Shadowserver reports approximately 50,000 vulnerable instances exposed to the internet.

- February 11, 2025: Fortinet updates the advisory to include CVE-2025-24472, acknowledging a related CSF (Security Fabric) vulnerability discovered by watchTowr.

Affected Versions & Patch Status

FortiOS:

- Affected: 7.0.0 through 7.0.16

- Fixed: Upgrade to 7.0.17 or above

- Not Affected: FortiOS 7.6, 7.4, 7.2, 6.4

FortiProxy:

- Affected: 7.0.0 through 7.0.19 and 7.2.0 through 7.2.12

- Fixed: Upgrade to 7.0.20+ (for 7.0 branch) or 7.2.13+ (for 7.2 branch)

- Not Affected: FortiProxy 7.6, 7.4, 2.0

The unaffected version list is interesting. FortiOS 7.2 and 7.4 dodged this bullet entirely, which suggests the vulnerable code was introduced in the 7.0 branch and wasn’t carried forward. This happens when someone rewrites functionality “the right way” in a newer version without realizing the old version was a security disaster.

Forensic Data Collection

- If virtual Forti –> Export the VMDK

- If baremetal –> Contact FortiSupport and request assistance. Will likely need to ship the device back to Forti for the image (We’ve seen success doing this)

- Try some Forti triage commands –> Secret gist

- Revert the Forti version and exploit it yourself to get a root session –> Generate a forensic image using your choice of dd* and collect memory using avml

Proof of Concept Information

Multiple public proof-of-concept exploits exist for this vulnerability:

watchTowr Labs PoC:

- Repository:

watchtowrlabs/fortios-auth-bypass-poc-CVE-2024-55591 - Python-based exploit that establishes an unauthenticated WebSocket connection to

/ws/cli/endpoint - Uses race condition techniques to inject authentication before the legitimate system authentication

- Includes detection capabilities and command execution functionality

- Requires knowledge of an admin username (default “admin” works on most systems)

The existence of reliable, working public exploits means that any script kiddie with Python installed can now compromise vulnerable FortiGate instances. The barrier to entry is approximately “can run python script.py” which is only slightly more challenging than breathing.

Technical Analysis: How The Exploit Actually Works

This is where things get interesting. Let’s walk through the vulnerability chain step by step, because this isn’t a single flaw but rather four security controls that all decided to take a vacation at the same time.

The Node.js Architecture

FortiOS uses a Node.js application to handle management interface functionality. The relevant code lives in /node-scripts/index.js, a sprawling 53,642-line JavaScript file that makes webpack bundles look organized. Within this mess is the code that handles the jsconsole feature, a WebSocket-based web console that provides CLI access through the management interface.

When you click the CLI button in the FortiGate web GUI, the following happens:

- Your browser establishes a WebSocket connection to the Node.js server

- The Node.js server establishes a Telnet connection to localhost port 8023 (the actual CLI process)

- The Node.js server acts as a proxy between your WebSocket and the Telnet CLI

- Authentication magic happens (or in this case, doesn’t happen)

Vulnerability Chain Component 1: Unauthenticated WebSocket Creation

The first problem is in the dispatch() function that handles WebSocket routing. When a request comes in to /ws/cli/, the code attempts to get a valid session:

async dispatch() {

const {session, isCsfAdmin} = await this._getSession();

if (!session) {

this._logError('Authorization failed. Closing websocket.');

this.ws.send('Unauthorized');

this.ws.close();

return null;

}

// ... continue with authenticated WebSocket setup

}

This looks fine at first glance. No session? No WebSocket. Unfortunately, the _getSession() function has some interesting ideas about what constitutes authentication.

Vulnerability Chain Component 2: The Magic local_access_token Parameter

The _getSession() function tries several methods to establish a valid session. If normal authentication methods fail, it falls back to _getAdminSession(), which is where things go sideways:

async _getAdminSession(request, options = {}) {

const { headers, url } = request;

const query = querystring.parse(url.replace(/.*\?/, ''));

const localToken = query.local_access_token;

// ... other authentication methods ...

else if (localToken) {

authParams[authParams.length - 1] += `?local_access_token=${localToken}`;

authParamsFound = true;

}

if (!authParamsFound) {

return null;

}

try {

return await new ApiFetch(...authParams);

}

}

Here’s the critical flaw: if you include any value for the local_access_token query parameter, the code sets authParamsFound = true and proceeds to make an API call. There’s no validation of the token. None. Zero. It doesn’t check if it’s valid, if it corresponds to a real session, or if it’s just the string “definitely_a_real_token_trust_me”.

The code essentially says: “Oh, you have a local_access_token parameter? Well, you must be legitimate then. Let me just ask the REST API if you’re cool.” And then it makes a REST API call to localhost.

Vulnerability Chain Component 3: REST API Trusts Localhost (But Shouldn’t)

When the code makes that REST API call to localhost, it’s supposed to validate the session. The problem is that the REST API sees the request coming from 127.0.0.1 (because Node.js is proxying it) and makes a dangerous assumption.

The REST API authentication mechanism for trusted local requests doesn’t properly validate the local_access_token parameter. It sees:

- Request from 127.0.0.1? ✓

- Has a local_access_token parameter? ✓

- Must be legitimate! ✓

No verification of the token value. No session validation. No authentication. Just vibes.

Vulnerability Chain Component 4: The Race Condition

Here’s where it gets spicy. Even with the authentication bypass, you still need to authenticate to the CLI process over the Telnet connection on localhost:8023. The Node.js code establishes this connection and sends a “login context” that looks like this:

"admin" "admin" "root" "super_admin" "root" "none" [192.168.1.1]:12345 [192.168.1.1]:443

This is the format: login_name admin_name vdom profile admin_vdoms sso_type forwarded_client forwarded_local

The code waits for the CLI to send a greeting message (“Connected.”) before sending this login context. But there’s a race condition: the WebSocket message handler is already active and accepting messages from the client before the greeting is processed.

ws.on('message', msg => cli.write(msg));

cli.setNoDelay().on('data', data => this.processData(data));

This means you can send your own authentication string to the CLI process via WebSocket before the legitimate authentication happens. If you win the race, the CLI authenticates you with whatever privileges you specified.

Exploitation Steps

Putting it all together, here’s how exploitation works:

- Establish WebSocket with bypass:

GET /ws/cli/?local_access_token=anything HTTP/1.1 Upgrade: websocket -

Wait for WebSocket upgrade response: The server establishes the WebSocket and creates the Telnet connection to the CLI.

- Race the authentication:

Immediately send your crafted login context over the WebSocket:

"attacker" "admin" "attacker" "super_admin" "root" "none" [13.37.13.37]:1337 [13.37.13.37]:1337 -

Win the race: If your authentication string reaches the CLI before the legitimate one, you’re authenticated with super_admin privileges. The CLI doesn’t validate these parameters; it just accepts them.

- Execute commands:

Now you have full CLI access. You can:

- Create admin accounts

- Modify firewall rules

- Add SSL VPN users

- Extract configuration

- Pivot to internal network

The race condition is relatively easy to win. The watchTowr PoC establishes multiple concurrent WebSocket connections and bruteforces the timing until one wins the race. On a typical system, this takes seconds.

Why This Is Actually Four Vulnerabilities

Let’s count them:

- Improper session validation: The

local_access_tokenparameter bypasses session checks with any value - Missing authentication in REST API: The localhost REST API doesn’t validate the token

- Race condition in WebSocket handling: Message handlers are active before authentication completes

- Insufficient validation in CLI authentication: The CLI process accepts authentication parameters without verification

Any one of these issues alone might have been caught. But together, they create a complete authentication bypass that’s both reliable and trivially exploitable.

The CSF Variant (CVE-2025-24472)

The February update added CVE-2025-24472, which exploits a similar vulnerability through the CSF (Security Fabric) proxy requests. This is essentially the same architectural flaw in a different endpoint. The patches for CVE-2024-55591 also address this variant, suggesting Fortinet did a more thorough review after watchTowr’s disclosure.

Forensic Considerations and Limitations

Now for the part that keeps incident responders awake at night: what forensic evidence does this attack leave behind, and what doesn’t it leave?

What You Might Find

1. Authentication Logs (If You’re Lucky)

Successful exploitation generates logs in the FortiGate system logs that look like legitimate admin activity, because from the CLI’s perspective, it is legitimate admin activity:

type="event" subtype="system" level="information" vd="root"

logdesc="Admin login successful" sn="[SERIAL]" user="admin"

ui="jsconsole" method="jsconsole" srcip=1.1.1.1 dstip=1.1.1.1

action="login" status="success" reason="none" profile="super_admin"

Notice the ui="jsconsole" field. In legitimate use, this is normal. During exploitation, this is your smoking gun. But here’s the problem: the srcip and dstip fields are completely attacker-controlled. Fortinet’s advisory lists these commonly observed IPs:

1.1.1.1,2.2.2.2,8.8.8.8,8.8.4.4,13.37.13.37,127.0.0.1

These aren’t real source IPs. They’re arbitrary values the attacker injects during authentication. The actual attack traffic comes from wherever the attacker is, but you won’t find that in these logs.

2. Admin Account Creation

Post-exploitation, attackers typically create persistent access by adding admin accounts:

type="event" subtype="system" level="information" vd="root"

logdesc="Object attribute configured" user="admin"

ui="jsconsole(127.0.0.1)" action="Add" cfgpath="system.admin"

cfgobj="vOcep" cfgattr="password[*]accprofile[super_admin]vdom[root]"

msg="Add system.admin vOcep"

The username vOcep is randomly generated by the attacker. Fortinet’s IoC list includes examples: Gujhmk, Ed8x4k, G0xgey, Pvnw81, Alg7c4, watchTowr, fortinet-support. Some attackers have a sense of humor.

3. SSL VPN User Creation/Modification

Attackers commonly create local users and add them to SSL VPN groups for persistent remote access:

type="event" subtype="system" level="information" vd="root"

logdesc="Object attribute configured" user="admin"

ui="jsconsole(127.0.0.1)" action="Add" cfgpath="user.local"

cfgobj="[RANDOM_USERNAME]"

Followed by user group modifications to grant VPN access.

4. Configuration Changes

Firewall policy modifications, address object creation, and other configuration changes will appear in logs, all attributed to jsconsole activity.

What You Won’t Find

1. Initial Attack Traffic

The WebSocket upgrade request that initiates exploitation is likely not logged by default FortiGate logging. Unless you have:

- Full packet capture at the network perimeter

- WAF or reverse proxy with detailed WebSocket logging

- Debug logging enabled on the FortiGate (which nobody does in production)

You won’t see the initial exploitation attempt. The first indication of compromise is typically the successful authentication log, which looks like legitimate admin activity.

2. Real Attacker IP Addresses

The IP addresses in the authentication logs are attacker-supplied fiction. The actual source IP of the attack requires:

- Network flow logs from upstream devices

- Correlation with WebSocket connections to the management interface

- Timestamp correlation (tricky because the attacker controls the clock in the auth logs)

3. Failed Exploitation Attempts

Failed race condition attempts might generate brief WebSocket connections that quickly close, but these likely aren’t logged as failed authentication attempts. The authentication failure happens at the CLI layer, which doesn’t know about the WebSocket connection.

4. Pre-Exploitation Reconnaissance

Standard port scans and version fingerprinting of the management interface leave minimal traces. The watchTowr detection script, for example, just attempts to establish a WebSocket connection and checks the response, which is barely distinguishable from legitimate browser activity.

What We’ve Observed In The Wild

Based on Fortinet’s advisory and Arctic Wolf’s analysis, real-world exploitation follows a consistent pattern:

Phase 1: Initial Access

- WebSocket exploitation via CVE-2024-55591

- Super-admin CLI access achieved

- Minimal logging, often just the jsconsole login event

Phase 2: Persistence

- Random admin account created (e.g.,

G0xgey) - Random local user account created

- Local user added to existing SSL VPN group or new group created

- All logged as normal admin activity via jsconsole

Phase 3: Lateral Movement

- SSL VPN connection established using newly created account

- This does generate VPN connection logs with real attacker IP

- Tunnel to internal network established

Phase 4: Post-Exploitation

- Firewall policy modifications (if needed for C2)

- Configuration backup extraction

- Credential harvesting from device configuration

- Pivot to internal systems

The real attacker IP typically only becomes visible during Phase 3 when they connect via SSL VPN. By this point, they have persistent access and you’re already compromised.

These are the real attacker IPs observed in VPN connections and post-exploitation activity, not the spoofed values in the initial authentication logs.

Forensic Response Recommendations

If you suspect compromise:

- Immediately review jsconsole authentication logs for logins you can’t account for, especially with suspicious IP addresses (

1.1.1.1,8.8.8.8,127.0.0.1, etc.) - Audit admin accounts for recently created users with random-looking usernames

- Check SSL VPN user lists for unauthorized local users or unexpected group memberships

- Review firewall policy changes made via jsconsole during the suspected compromise window

- Examine SSL VPN connection logs for connections from unknown IPs using recently created users

- Extract full configuration backup for offline analysis of all changes

- Correlate timing between jsconsole activity and external SSL VPN connections to identify the real attacker IP

- Assume compromise if: You find admin accounts you didn’t create, SSL VPN users you don’t recognize, or any jsconsole activity during off-hours from accounts that should have been idle

The harsh reality: if your FortiGate was vulnerable and exposed, and you can’t definitively prove it wasn’t exploited, you should probably assume it was.

Forensic Evidence Collection

When exploitation is suspected or confirmed, evidence collection needs to happen fast. FortiGate logs rotate, memory is volatile, and attackers with admin access can disable logging or wipe evidence. The following methods preserve forensic artifacts before they disappear.

Collection Priority Order

Time matters. The forensic window closes fast. If you can’t collect everything immediately:

- System logs - Rotate fastest, contain authentication and admin action evidence

- Memory dump - Most volatile, shows active sessions and in-memory configurations

- Configuration backup - Shows what the attacker could access or modify

- Disk image - Time-consuming but comprehensive preservation

- Network flow logs - May show data exfiltration or C2 communication

- External SIEM data - If forwarding was enabled and not disabled by attacker

Logs rotate. Sessions expire. Attackers clean up. Collect what matters first.

FortiGate Log Extraction

FortiGate devices store logs in memory and disk depending on configuration. Critical for investigations because they contain the only evidence of SSO authentication and post-compromise actions.

Export all event logs:

# Via CLI - exports to TFTP/FTP server

execute backup disk full-config tftp <filename> <tftp_server_ip>

# Export system logs to USB (if available)

execute backup disk full-log usb <filename>

# Export logs via SCP (requires SSH enabled)

execute backup disk alllogs scp <filename> <scp_server_ip>:<path> <username>

Export specific log categories:

# Export only system event logs (authentication, admin actions)

execute log filter category 0

execute log filter field subtype system

execute log display

execute log export tftp <filename> <tftp_server>

# Export traffic logs (network connections)

execute log filter category 1

execute log display

execute log export tftp <filename> <tftp_server>

# Export security logs (IPS, AV, etc.)

execute log filter category 2

execute log display

execute log export tftp <filename> <tftp_server>

Check log storage locations:

# Show current log storage settings

diagnose sys top-summary

# Check disk space and log usage

get system status

# Show logging configuration

show log setting

show log syslogd setting

show log fortianalyzer setting

If using FortiAnalyzer or Syslog:

Logs may be preserved externally even if local logs are cleared:

# Check if FortiAnalyzer is configured

get log fortianalyzer setting

# Check if syslog forwarding is active

get log syslogd setting

# Verify last successful log upload

diagnose test application miglogd 4

If external logging was active, immediately secure those log stores before the attacker accesses them.

Memory Acquisition

Memory contains active sessions, cached credentials, in-memory configurations, and runtime state that doesn’t exist on disk. For FortiGate investigations, memory is critical because it may contain:

- Active admin session tokens and cookies

- SAML response processing artifacts

- Cached configuration changes not yet written to disk

- Network connection states

- Process memory showing what the attacker accessed

Physical FortiGate Appliance Memory Dump:

FortiGate devices run FortiOS (a hardened Linux kernel). Direct memory access requires specific procedures:

- Remember that ProcFS is mounted and you can review it via fnsysctl cat/ls commands

# Check available memory

diagnose hardware deviceinfo mem

# Enable core dump (requires reboot)

diagnose debug enable

diagnose debug core-dump enable

# Trigger controlled crash to generate core dump (USE WITH EXTREME CAUTION)

# This will reboot the device - only use if authorized

diagnose debug crash

Core dumps are stored in /data/core/ and can be extracted via SCP or USB.

VM-based FortiGate (FortiGate-VM) Memory Dump:

For virtual appliances, use hypervisor snapshot capabilities:

# VMware ESXi - suspend to capture memory

vim-cmd vmsvc/power.suspend <vmid>

# Memory saved to .vmss file in VM directory

# Resume after copying: vim-cmd vmsvc/power.on <vmid>

# Hyper-V memory dump

Stop-VM -Name FortiGateVM -Save

# Memory saved to .bin and .vsv files

Start-VM -Name FortiGateVM

# KVM/QEMU memory dump

virsh dump <domain> /forensics/fortigate-memory.dump --memory-only --live

# AWS EC2 (if EBS-backed)

# Create snapshot, then extract from snapshot volume

aws ec2 create-snapshot --volume-id vol-xxxxx --description "FortiGate forensics"

Alternative: Configuration and Session State Extraction:

If full memory dump isn’t possible, extract runtime state:

# Dump current configuration (includes all settings)

show full-configuration

# Show active admin sessions

diagnose sys session list

# Show cached certificates and keys

diagnose vpn ssl list

# Show SAML configuration and status

diagnose debug application samld -1

diagnose debug enable

# Let it run for 30 seconds to capture SAML processing

diagnose debug disable

diagnose debug reset

Disk Imaging

Disk images preserve FortiGate system files, logs, configuration, and forensic artifacts. For disk imaging captures:

- Complete log history before rotation (

/var/log/) - System configuration files (

/data/config/) - Certificate stores and private keys

- Historical configuration versions

- System binaries and potential persistence mechanisms

Physical Appliance Disk Imaging:

Physical FortiGate devices use internal storage (SSD/HDD). Imaging requires physical access; if this is impossible or risk is not accepted to crack open the device; consider working with FortiSupport to have a bitwise image generated after shipping the entire device

# Using dc3dd (forensically sound)

sudo dc3dd if=/dev/sdb of=/forensics/fortigate-disk.img hash=sha256 log=/forensics/imaging.log

# Using dd and dumping output to a remote host (Few methods)

dd if=/dev/<source> bs=16M | ssh <user>@<host> “/bin/dd of=/path/to/save/<device_name>.dd bs=16M”

dd if=/dev/<root device> bs=5M conv=fsync status=progress | gzip -c -9 | ssh <user>@<DestinationIP> 'gzip -d | dd of=<device_name>.dd bs=5M'

VM-based FortiGate Disk Imaging:

For virtual appliances, snapshot the virtual disks:

# VMware - Clone VMDK files

vmkfstools -i fortigate.vmdk fortigate-forensic.vmdk

# Hyper-V - Export VM disks

Export-VM -Name FortiGateVM -Path C:\Forensics\

# KVM/QEMU - Copy qcow2 images

cp /var/lib/libvirt/images/fortigate.qcow2 /forensics/fortigate-forensic.qcow2

# AWS EC2 - Create AMI or snapshot

aws ec2 create-image --instance-id i-xxxxx --name "FortiGate-Forensic-Image"

# Or snapshot specific volumes

aws ec2 create-snapshot --volume-id vol-xxxxx --description "FortiGate forensics"

# Azure - Create managed disk snapshot

az snapshot create --resource-group myRG --name fortigate-snap --source /subscriptions/.../disks/fortigate-disk

# GCP - Snapshot persistent disk

gcloud compute disks snapshot fortigate-disk --snapshot-names=fortigate-forensic --zone=us-central1-a

Live Backup (If Device Can’t Be Taken Offline):

If the FortiGate must remain operational:

# Full configuration backup (includes encrypted passwords)

execute backup full-config tftp backup.conf <tftp_server>

# Or via SCP (preferred for security)

execute backup full-config scp backup.conf <user>@<server>:<path>

# Full disk backup (includes logs, firmware)

execute backup disk full-config tftp full-backup.img <tftp_server>

# Verify backup integrity

execute restore verify tftp backup.conf <tftp_server>

Configuration Files

Configuration reveals what was enabled during the exploitation window and what the attacker could access or modify.

Critical FortiGate configurations:

- Full system configuration (contains all settings, VPN configs, certificates)

- SAML SSO configuration (IdP settings, certificate trusts)

- Admin account configurations (users, permissions, trusted hosts)

- Logging configuration (shows if attacker disabled logging)

- VPN configurations (IPsec, SSL-VPN credentials)

- Certificate stores (private keys, CA certificates)

Triage Extract via CLI: For a starting triage and forensic command reference, see our FortiGate triage command collection at https://gist.github.com/gottlabs/4fdc425bd8c50944e9a5c67806d7639c. It includes system integrity checks, process enumeration, filesystem inspection, and network state collection commands useful during incident response.

Configuration file locations on disk:

/data/config/sys_global.conf- Global system configuration/data/config/fgt.conf- Main FortiGate configuration/etc/init.d/- Service configurations/data/- Data directory containing logs and configs

System logs and forensic artifacts:

/var/log/log- Main event log file/var/log/log.*- Rotated log files/data/var/log/- Persistent log storage/var/log/message- System messages/var/tmp/- Temporary files (may contain session data)

Certificate and key stores:

/data/etc/cert/- Certificate storage/data/etc/ssl/- SSL certificates and keys/etc/cert/- System certificates

External SIEM/Log Aggregation

If FortiGate was forwarding logs to external systems:

FortiAnalyzer logs:

- May contain complete event history even if local logs cleared

- Check for SSO authentication events with method=”sso”

- Review configuration change logs

- Analyze traffic logs for post-compromise behavior

Syslog servers:

- Preserve logs even if FortiGate compromised

- Search for logid 0100032001 (admin login) with method=”sso”

- Search for logid 0100032095 (config download)

- Correlate with other security events

Detection and Hunting

Let’s talk about detection strategies, both for identifying vulnerable systems and hunting for evidence of exploitation.

Network-Based Detection

WebSocket Connection Monitoring

The most reliable indicator during exploitation is the WebSocket upgrade request to /ws/cli/ with a local_access_token parameter:

GET /ws/cli/?local_access_token=[ANYTHING] HTTP/1.1

Host: [target]

Upgrade: websocket

Connection: Upgrade

Sec-WebSocket-Key: [base64]

Sec-WebSocket-Version: 13

If you have:

- WAF logs in front of FortiGate management interfaces

- Reverse proxy with WebSocket visibility

- Full packet capture

Look for WebSocket upgrade requests to /ws/cli/ that:

- Include

local_access_tokenparameter - Come from non-administrative source IPs

- Occur outside normal maintenance windows

- Are followed by immediate WebSocket data exchange

SOC Prime has released Sigma rules for detecting these patterns in web server logs. The rule looks for:

- HTTP GET or POST methods

- URI path containing

/ws/cli/ - Query string containing

local_access_token

Vulnerability Scanning

The watchTowr detection script can identify vulnerable instances without exploitation:

python fortios-auth-bypass-check.py --target [IP] --port 443

This script:

- Attempts WebSocket upgrade to

/ws/cli/ - Checks if upgrade succeeds without authentication

- Does not attempt exploitation

- Returns true/false for vulnerability status

Organizations can use this to inventory their FortiGate fleet and prioritize patching. Network security teams can use it to identify rogue or forgotten FortiGate instances.

Host-Based Detection (FortiGate Logs)

Suspicious jsconsole Activity

Hunt for authentication events with jsconsole as the UI:

ui="jsconsole" AND (srcip="1.1.1.1" OR srcip="8.8.8.8" OR srcip="13.37.13.37" OR srcip="127.0.0.1" OR srcip="2.2.2.2")

These spoofed IPs are common attacker choices. Legitimate jsconsole activity typically shows the actual management interface IP.

Also hunt for jsconsole activity:

- During off-hours

- From admin accounts that were logged in elsewhere simultaneously

- Immediately followed by account creation

- With usernames that don’t match your naming conventions

Admin Account Anomalies

Look for account creation events:

action="Add" AND cfgpath="system.admin" AND ui="jsconsole"

Filter for:

- Random or unusual usernames (short alphanumeric strings)

- Accounts with super_admin profile

- Creation during suspicious timeframes

- Accounts you didn’t authorize

SSL VPN User Activity

Search for local user creation or modifications:

cfgpath="user.local" AND action="Add"

cfgpath="user.group" AND action="edit"

Followed by SSL VPN connections from these users:

type="event" subtype="vpn" logdesc="SSL VPN tunnel up"

The VPN connection logs will contain the real attacker IP address.

Remediation and Workarounds

Let’s talk about how to actually fix this mess and what to do if you can’t patch immediately.

Primary Remediation: Patch

FortiOS:

- Upgrade 7.0.0 through 7.0.16 to 7.0.17 or higher

FortiProxy:

- Upgrade 7.0.0 through 7.0.19 to 7.0.20 or higher

- Upgrade 7.2.0 through 7.2.12 to 7.2.13 or higher

Use Fortinet’s upgrade tool at https://docs.fortinet.com/upgrade-tool to determine the correct upgrade path. Don’t skip versions unless the upgrade tool explicitly says it’s safe.

Important: The patches for CVE-2024-55591 also fix CVE-2025-24472 (the CSF variant), so you’re killing two vulnerabilities with one firmware upgrade.

Closing Assessment

This vulnerability is bad. It’s being exploited in the wild. It’s trivial to exploit with public proof-of-concept code. It affects tens of thousands of exposed devices. It compromises perimeter security, which is the worst kind of compromise.

If you run FortiGate, patch now. If you can’t patch immediately, implement the workarounds now. Then hunt for evidence of compromise. Then update your security architecture to never expose management interfaces to the internet again.

And if you find evidence of compromise, don’t just patch and move on. Assume lateral movement, hunt throughout your environment, and respond as if your perimeter was completely bypassed. Because it was.